Chronic labor law violations: the real cost of Sino-Venezuelan joint ventures

Ilustration by: Alonso Gañan.

The partnership with China promised to turn Venezuela into a Latin America power. Yet two decades, 468 agreements and over $67bn later, agreements with one of the principal exponents of Chavismo have placed the country at a significant disadvantage. The relationship ended heavily in favor of Asia’s largest economy, leaving Venezuela with a vulnerable labor force, billion dollar debts, and a series of half-finished projects.

“The legacy of our Supreme Commander, Hugo Chávez, is continued by President Nicolás Maduro,” announced the then vice president Elías Jaua, against the backdrop of the mountainous valleys of the Miranda State, in the center of the country. during a broadcast on state television, Jaua announced in February 2014 that work would commence on the Santa Lucía-Kempis highway, a section of the ambitious Valles del Tuy road Integration project, which offered the promise of connecting the east of the country to the west through a major road corridor that would create 610 direct jobs.

“No-one can be bothered to start this project. Come and work with us, but you’ll have to keep up!”, joked Jaua during his speech.

Soon after, Venezuelan engineer Enrique Chacón* began working with Chinese construction company Sinohydro on the new highway project. He had previously worked with China’s transnational companies and was familiar with the contracting scheme that some Venezuelans describe as “Made in China”, referring subcontracting and other practices that violate the country’s Organic Law of Labor and Workers (LOTTT).

The project, according to Jaua, had been conceived years before, but the Fourth Republic, a term chavistas use to refer to the period of democracy from 1956-99, “never carried it out”. The idea of a highway that would connect the states of the country’s north-central region without congesting Caracas, he recalled, was salvaged by Chávez while stuck in a traffic jam when trying to enter the capital.

Enshrined in a bilateral agreement between China and Venezuela, the multimillion-dollar project was estimated to benefit some six million people, or a fifth of the population, according to official data available at the time. In the heart of Miranda State, the Santa Lucía-Kempis section of the highway alone involved an investment of four billion bolivars (roughly equivalent to $45.58m) and was set for completion in 2015.

Six years after Jaua’s declarations, any traces of the promised highway have been consumed both by thick vegetation and organized crime. Reports of corruption, development promises, and labor violations suffered by workers – including Chacón – in this and other projects of the agreement, remain buried. The project, never completed in the Fourth Republic, was barely 40% completed during the Chavéz administration.

China’s evasion of labor laws

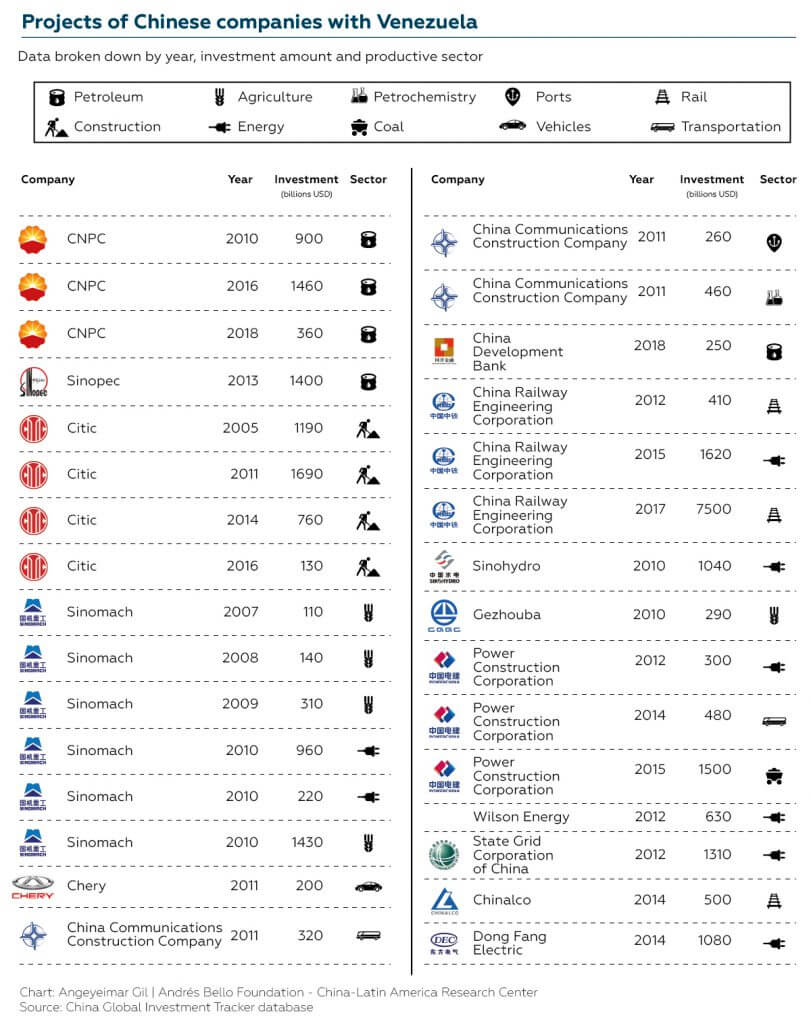

An investigation conducted by Venezuelan academic Angeyeimar Gil for the China-Latin America Research Center Fundación Andrés Bello (FAB) found that the outsourcing of personnel from third parties is one of the most common practices of Chinese companies in Venezuela.

For the development of the Valles del Tuy Highway Integration program, Sinohydro and Brazilian conglomerate Camargo Correa (now Mover Participações), subcontracted personnel through the company Consorcio Santa Lucía-Kempis until it ceased operations in 2017. This clearly contravenes article 48 of the LOTTT prohibiting “outsourcing”, as this method of labor law evasion is known.

The same methods have been reported by workers subcontracted by other Chinese companies. Such is the case of the construction company Gezhouba Group Corporation, responsible for agrarian projects throughout the vast Llanos plains in the central, southern, and southwestern parts of the country, which contracted personnel through Venezuelan company Constructora La Lucha 168.

Owned by Chinese and Venezuelan nationals, Constructora La Lucha 168 used this scheme for a project with Harbor Engineering Company LTD, a Chinese company that signed a memorandum of understanding in 2010 to develop a new terminal for containers in Puerto Cabello, the country’s largest seaport located in Carabobo State. With the promise of creating 360 roles and over 2,500 indirect Jobs, the project was worth $600m.

“Constructora La Lucha 168 was a contractor in almost all the projects that the government had with China”, explains Chacón. Despite participating in works carried out under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture and Land, the state agency in charge of a housing policy called the Great Venezuela Housing Mission, and state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), there are no official public records relating to its relationships with any transnational companies.

Although domiciled in Venezuela, Constructora La Lucha 168’s footprint extends as far as the South China Sea. The company was registered in Hong Kong in March 2014, just two months after Jaua’s announcement. According to local company registry records, the company was dissolved on May 10, 2019.

A correlation of disadvantages

“In the case of the Santa Lucía-Kempis project, 20% of the labor force was Chinese, 40% Brazilian and the rest were from Venezuela. The most senior positions were held by foreigners, and there were even duplicate positions. Why did we end up, for example, having a Chinese and a Brazilian coordinator?”, asks Chacón. “In the end everything ground to a halt with less than half the project completed”.

Gil’s research also addresses labor patterns that point to Chinese companies having payrolls that are mostly made up of Chinese workers. This practice puts local personnel at a disadvantage and contravenes Venezuelan law, which states that the proportion of foreign workers cannot exceed 10%.

The salary gap between foreign and local employees highlights another disadvantage imposed by the agreements, despite the training and relevant professional experience of the latter. Chinese personnel received a salary of over $2,000, while Venezuelans, as was the case with Chacón, were limited to an equivalent of roughly $312 at the exchange rate of the time.

“Because of the mountainous terrain in the Miranda State section of the project, I remember one contractor saying that it would be preferable to build a tunnel. But the representatives of the transnational company said no, as they would be able to charge more if they did it another way. They defended their decision based on their own Chinese building criteria, but we have our own standards. They failed to recognize the experience of Venezuelan workers”, laments Chacón, who finally emigrated to Ecuador in 2016 to escape the ongoing crisis. Finding work in his sector over 1,500 kilometers from home was the only way for Chacón to support his family, still based in Venezuela.

Another complaint brought against the companies involved in the agreement’s projects is the lack of any independent union. This practice, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO) and other associations of workers, human rights, and labor, is a Chinese export, whose legislation restricts the freedom of workers’ unions and prevents the formation of independent unions. They are subordinate to the All-China Federation of Trade Unions.

The right to freedom of association has been a sensitive topic between China and the ILO. The Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, and the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, established in 1948 and 1949 respectively, are two of the four fundamental ILO agreements that China has refused to recognize.

“I never heard of a union within Constructora La Lucha 168. The Chinese just don’t like that sort of thing”, explains Andrés Lara*, a young lawyer who worked at the Caracas headquarters of China National Petroleum Corporation in 2018.

Restricting the formation of unions is another practice that contravenes Venezuelan law, which establishes the right of workers to form free unions.

“They were very shrewd. To comply with the LOTTT, the Chinese companies created unions, yet in reality they didn’t function as such. They appointed the same Chinese workers to form a group, but in the end, the unions favored the employer”, says Chacón.

Old links, new debts

The relationship between China and Venezuela is not a new phenomenon. In June 1974, both countries strengthened diplomatic ties after Venezuela formally acknowledged the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party. Since then, and especially since Chavez’ rise to power in 1999, both countries have signed at least 20 bilateral agreements.

With the arrival of Chavismo, the Sino-Venezuelan partnership flourished. The fruits of this union took the form of multimillion-dollar contracts to develop areas of interest that were largely in China’s favor, including gas, oil, and minerals.

Over the past two decades, this relationship has established over 500 agreements, according to official sources. In 2016, Caracas confirmed no fewer than 672 projects with China. 388 of these had been completed, 203 were in the implementation phase, and a further 131 had only recently been agreed. However, data compiled by anti-corruption watchdog Transparencia Venezuela, part of Transparency International, together with Venezuelan open data platform Vendata, identify only 468 agreements from 1998 to 2019.

Opacity is a defining characteristic of the Sino-Venezuelan relationship. According to Transparencia, the terms on which 64.81% contracts with China have been signed are unknown, while in 22.42% of the cases there is only partial information. The details of just 12% of the agreements are publicly known.

In addition to labor law violations and other disadvantages, the bilateral relationship has essentially mortgaged the country’s future. According to data published by Washington think-tank Inter-American Dialogue and Boston University, Beijing lent Venezuela over $67bn between 2007 and 2018. Approximately 90% of the debt is to be paid in oil and through Chinese imports. It is estimated that Venezuela still owes around $20bn.

“The conditions offered by Venezuela in these agreements opened the doors to investment and the installation of Chinese companies in the country. These conditions, as is the case in several other Latin American countries, are not at all beneficial for the recipient country. For one thing, foreign labor is prioritized at middle and senior levels, in addition to other elements”, explains Gil.

Venezuela is not the only country in the region to have witnessed an exponential growth in Chinese investment on home soil. Since 2000, China has become a key partner for Latin America, reaching a peak in 2016 when 11.81% of the region’s foreign direct investment originated from the Asia giant.

Similar to Venezuela’s experience, these investments have not necessarily translated into well-paid jobs with basic conditions for local populations.

Regional governance platform Collective on Chinese Finance and Investment, Human Rights and the Environment (CICDHA) reports at least 12 labor violations in Latin America such as the dismissal of workers for demanding better conditions, or limitations on the establishment of trade unions. All of these infractions took place in companies linked to the mining, hydroelectric and oil sectors.

No economic development, no prosperity

In 2017, Fernando Arenas* began working for Chinese technology company ZTE, which supplies electronic surveillance services to Chinese household appliance producer Haier. Yet despite working with two multinational companies, his hiring process was oral, and never formalized during the year he worked at the San Francisco de Yare plant in Miranda State.

The hiring was carried out by Venezuelan telecommunications and engineering company Cellnetca, which has offices in Panama City, Bogota, and Miami. Beyond the information published on the contractor’s website, there are no public records concerning its activities with Chinese companies.

“There was a colleague I had worked with at Alcatel. After the company left Venezuela, he went to ZTE and contacted me to work together. I’m an engineer, and the hiring took place under strange conditions that I’ve never really understood. There was no signed contract. I didn’t have a work permit. I didn’t even know the name of my boss”, explains Arenas, who worked with ZTE for a year and three months.

In the absence of any formal contract, none of the basic benefits stipulated in the LOTTT, such as insurance, bonuses, and vacations, were available for workers.

Exchange controls were officially announced in Venezuela in 2003, and in 2004 Chávez proceeded to devalue the bolivar, the official currency. What followed was a currency crisis that would generate at least 15 devaluations and two changes to its coinage. In 2017, the bolivar lost at least a thousand percent in value, and the use of the United States dollar became commonplace in private contracts and other businesses as a preservation mechanism in the face of constant devaluation. But this was never carried out publicly.

At the time, the use of the dollar was prohibited, and there was no access to foreign currency accounts. Yet Arenas received his payments in dollars, and along with other workers who like him only had Venezuelan bank accounts, he had to coordinate with third parties who had bank accounts abroad, or with exchange platforms, to receive regular payments.

In the case of ZTE, Arenas believes that around 20% of the workers were Chinese nationals. Furthermore, the work environment within the plant was one of “apartheid”, and that local employees only held intermediate or low level positions.

“We never mixed. Venezuelan workers didn’t hold senior positions. Foreigners were the only ones in charge of any technical elements. They were qualified, but there were Venezuelans who could have carried out the same jobs”, he says.

What Arenas regrets most about his time at the company is not the labor violations, but the scale of Chinese investment into the commercialization of electrical appliances in Venezuela, which ended up being abandoned. In total, the Venezuelan government invested $800m of Chinese loans to build the Haier industrial complex.

“There were five huge warehouses. To move around the plant, you had to use a little car. There were refrigerators, stoves, washing machines, and televisions, all brought from China and checked in Venezuela. But it has all stalled. The technical reason is that the plant never had enough energy to begin operations at full capacity, as it needed an electrical substation. But the real reason it hasn’t started is political. There’s just no will to make things work”, said Arenas.

In November 2012, the then Minister of Industries, Ricardo Menéndez, announced that the first phase of the Haier industrial complex had the capacity to assemble 815 thousand household appliances, accounting for 70% of Venezuela’s demand for refrigerators and 63% of its washing machines. He even went so far as to say that the factory had the potential to export household appliances to countries in the Mercosur and Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) trade blocs, even to Europe and Africa.

Eight years after Menéndez’ grand announcements, the facility remains frozen. The goal of offering white goods, not to mention the creation of 104 direct jobs with guarantees of quality of life and basic conditions for local workers, exists on paper only.

After his experience with ZTE and Cellnetca, Arenas now works with a telecommunications company that respects “all the conditions enshrined in Venezuelan law”.

“Not only has the bilateral relationship left Venezuela at an economic disadvantage, it has both deepened existing and imported new forms of labor rights violations. These combine to bring profoundly negative consequences”, says Gil.

The tone set by Jaua during the inauguration of the Miranda State projects has a distinctly Asian feel. It is a rhythm accompanied by the LOTTT evasions, foreign versus local labor wage gaps, employers’ unions and debts paid through service contracts. “They paid themselves, then pocketed the change,” as the Venezuelan saying goes.

While Venezuela still owes China more than $16bn, according to data published by the Andrés Bello Foundation, the development of Puerto Cabello, the white goods facility in San Francisco de Yare in Miranda State, and the highway connecting the east and west of the country continue to be promises made by the agreement that have yet to find a positive balance for the Venezuelan economy.

* The names that appear in this article have been changed at the request of interviewees for fear of reprisal

Translated by Edward Longhurst-Pierce