COVID-19 aid from China to Latin America twice that of US as it increases investments in the region

Illustration by Alonso Gañán

The global paralysis caused by COVID-19 has brought the world economy into crisis. Yet amid such adversity, China has increased its capital export to Latin America through what analysts have dubbed “mask diplomacy.” Donations of medical supplies to the region in excess of $380m have been the instrument of its latest phase of expansion. Linked in some cases to the concept of guanxi (关系)—the networks of trust and reciprocity of Chinese philosophy—the stage is now being set for further expansion and the continuing battle for global leadership.

As countries adjust to the COVID-19 “new normal”, and as markets continue to contract and economies struggle to sustain themselves, one nation has seized the opportunities created by the pandemic while gaining a reputation of Good Samaritan. President Xi Jinping’s China has been in the global spotlight throughout this crisis, and not only because the virus originated in its territory, but because of the rapid mobilization of donations and support to some of the world’s most disadvantaged countries.

In a region such as Latin America with its precarious health systems, a proven strategy is repeated. Public or private entities from China donate supplies, and in turn the same recipients buy more supplies from China, strengthening burgeoning relationships in political and economic matters.

China offers a message of brotherhood and solidarity. In Argentina for example, it embodies this idea through poems on the same boxes that carry donations. Analysts however warn that beyond simple good will, it combines both innovation and the tradition of guanxi. It is a future plan. What is more, this “mask diplomacy”, as such expansion has been dubbed, shows no signs of abating. Meanwhile, the public face of China, its public and private companies, forge ahead.

Beyond corporate social responsibility

A week after the first case of COVID-19 in the United States, the well-known Chinese billionaire and philanthropist Jack Ma—who’s fortune is estimated at $42.3bn, according to Forbes magazine—offered $14.26m to halt the global outbreak of the new disease.

“Our united will to fight against the epidemic situation of novel coronavirus pneumonia is stronger than a fortress”, read a statement from his eponymous foundation.

The funds were directed to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Engineering and other institutions. New donations, both financial and supplies, soon followed, especially to Latin American countries.

Under the slogan “One world, one fight!”, the Jack Ma Foundation announced in March 2020 the donation of two million face masks, 400,000 rapid tests and 104 ventilators for intensive care units to 24 countries in Latin America. “We will ship long–distance, and we will hurry! We are one!” exclaimed the press release.

Accompanied by slogans of solidarity, China’s donations, beyond those offered by Jack Ma, began to span the world from March this year. Private companies from China were notable donors. Of the total donations made by China’s private companies since the outbreak of COVID-19, the majority went to Sub-Saharan Africa, the central axis of Chinese foreign policy under President Xi Jinping since 2013, notes consulting firm RWR Advisory Group. This is explained by foreign policy analyst Parsifal D’Sola, director of the Andrés Bello Foundation, a Latin American organization dedicated to researching Chinese relations and investments in Latin America.

“Since Xi Jinping’s election, part of China’s strategy has been to adopt a more aggressive foreign policy and a more assertive political stance vis-à-vis the West. There has been a sustained effort to win support in developing countries, particularly in Africa and Latin America. It is easier for China to penetrate these markets, and we are seeing this now with COVID-19,” explains D’Sola.

At the opening of the World Health Assembly on May 18 this year, Xi Jinping announced that China would allocate more than $2bn over a two-year period to help countries affected by COVID-19. He emphasized that such aid would focus in particular on developing countries.

“If China can gain friends among the decision-makers of these countries, it translates directly into votes of support in regional and multilateral institutions. This helps avoid any criticism of the Chinese Communist Party on its human rights track record, on Hong Kong, and on issues of sovereignty with Taiwan, among other areas. This is further highlighted by the unwritten, unbreakable rules that apply to China’s private sector companies sending donations. The Jack Ma Foundation has made no donations to countries that have relations with Taiwan, for example,” D’Sola points out.

China has become much more vocal in the global governance of medical issues since President Donald Trump formally moved to withdraw the US from the World Health Organization (WHO). “Every time the US leaves an international organization, China and other countries take those places,” says Margaret Myers, director of the Asia & Latin America Program at US think-tank Inter-American Dialogue, in an interview with the NTN24 channel.

Academics and analysts point out that donations from China are part of a wider political strategy labelled “mask diplomacy” that seeks to expand its influence worldwide.

On the surface, this looks like a foreign policy of cooperation and aid by China towards countries dramatically affected by the pandemic, especially many in Latin America that lack robust health systems.

It is however a policy of two dimensions, according to academics Florencia Rubiolo and Javier A. Vadell. The first is based on what American academic Joseph Nye, a promoter of the neoliberalism theory of international relations, calls the soft power in which discursive, symbolic and cultural elements of Beijing’s cooperation policy are incorporated in order to look good in the eyes of the world. The second, and most tangible, includes the provision of medical equipment, supplies, and other items.

Silent progress

The relationship between China and Latin America has advanced sufficiently to make it one of the region’s main trading partners. Direct investment from China to Latin America totaled $7.03bn between 1990 and 2009, and exceeded $64bn between 2010 and 2015, according to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

Latin American exports to China consist predominantly of raw materials rather than manufactured products, including soybeans, iron, oil, and copper, in order of importance. Conversely, China’s exports to Latin American include telecommunications, electrical and data processing equipment, optical instruments, and transportation, among others.

China surpassed the US as a buyer of raw materials in 2010, according to Kevin Gallagher of Boston University.

In the race for Latin American markets, COVID-19 has presented a welcome opportunity for Chinese companies to expand their commercial footprint in the region amid political tensions between Beijing and the White House, according to Evan Ellis of the US Army War College Strategic Studies Institute.

By filling the value chain gaps left by Western firms through the purchase of assets in the region, Chinese companies are set to transform relations with the continent. This process could prompt the US government to view these commercial advances with increasing concern”, notes Ellis.

In a rumbustious speech directed towards China delivered on March 18, US President Donald Trump referred to the pandemic as a “Chinese virus”, an expression he repeated on several occasions despite warnings made by the WHO to avoid any ethnic associations with the outbreak, as they risked supporting racial discrimination. Echoing Trump, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo went on to warn of the dangers that adopting 5G technology from Chinese telecommunications company Huawei posed for Latin America.

“The growing polarization between the US and China will make any trading partners heavily involved with the US more wary when it comes to entering into contracts with China, although many companies will attempt to seek benefits from both partners, given their similar status as super powers,” Ellis indicated.

“Donald Trump’s behavior has left much to be desired, especially in Latin America, and faced with this power vacuum, China is taking advantage. All humanitarian aid comes at a price, and seeing how the region has been affected economically and socially by the pandemic, China could help the recovery of Latin America,” signals Dr. Manfred Wilhelmy von Wolff, executive director of the Center for Advanced Studies and Extension (CEA) of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso in Chile.

In Latin America, Chinese aid during COVID-19 has surpassed that of the US, according to data compiled by the Wilson Center.

Based on the estimated prices of medical-surgical supplies listed on global e-commerce site alibaba.com, and of medication on global pharmaceutical site drug.com, the total amount of physical donations made by both countries across the region are showed on the following graph.

Click here to see the complete chart of donations from China to LAC.

While the data are not exact due to the margin of variability of the calculations, they help us to better visualize the reach that donations have had for both countries. Based on these figures, we can see that China has donated more than twice that of the US to combat the effects of the pandemic in Latin America.

According to these calculations, Chinese aid was close to $380 million, while that of the US was around $150 million. It is worth noting that while China donated far more overall, the US provided aid to all countries. In line with official policy, China did not provide support to countries enjoying diplomatic ties with Taiwan, including Belize, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Saint Lucia, Saint Kitts and Nevis and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

Paraguay and Nicaragua, caught between China and Taiwan

China’s efforts to enter markets such as Paraguay have not stopped, but it conditions its agreements on switching diplomatic relations from Taiwan to China. While the President of Paraguay Mariano Abdo insists he will not let himself be conditioned, left-wing parties and union forces continue to highlight the importance of having a commercial partner such as China.

In the midst of the pandemic, the Paraguayan senate rejected a draft declaration proposed by Guasu Front-led leftist parties in April this year urging the Abdo government to make a political rapprochement with China in exchange for health aid in the fight against COVID-19.

One argument offered by leaders was that Xi Jinping’s government had managed to contain COVID-19 in Wuhan. “[China] has sufficient supplies and personnel to face the pandemic (…) For Paraguay, these will serve not only for this crisis, but to address the ongoing shortfall of intensive care beds,” claimed legislators.

The Paraguayan Ministry of Health had already purchased medical supplies from Chinese companies, but these were mired in controversy. In the first instance, Paraguay reported that items purchased in April this year had been defective. The following month, the national comptroller indicated that the government had terminated the COVID-19 supply contracts it had in place with those companies, due to alleged irregularities.

In June, the left-wing faction of the Guasu Front managed a donation of 600 kilograms of medical-surgical supplies from China through Paraguay’s consulate in São Paulo, Brazil.

Taiwan meanwhile has reiterated its commitment to Paraguay, offering multi-million dollar donations. On April 2, Paraguay’s public health minister accepted the delivery of $3.2m worth of sanitary equipment from the Taiwanese government, and in May, another large donation was received that included 1.5 million masks, 50 electric beds, and 13 respirators, together with other supplies.

It may come as no surprise that a logistical route for the export of meat was created between Paraguay and Taiwan shortly afterwards in June, and completed in August when the first shipment arrived in Taiwanese supermarkets.

Nicaragua has also been strengthening its relationship with Taiwan. A report by news platform Connectas shows how Taiwan has become a “contradictory ally” for Nicaragua, calling for democracy and freedom for its own country, while developing linkages with a government accused of irregularities surrounding its perpetuation of power and human rights violations.

Yet Nicaragua is atypical. Despite its close relations with Taiwan, the concession for the Nicaragua Canal, one of the largest proposed projects in Central America (now cancelled due to allegations of corruption and not fulfilling environmental standards of construction), was granted by the Sandinista government to Chinese company HK Nicaragua Canal Development Investment (HKND). Analysts believe that this is not so much a shift in Nicaraguan foreign policy favoring China over Taiwan, but reflects Nicaragua’s aspirations of securing Chinese investment. This certainly seems to show Chinese interest being aligned with its trade expansion policy.

During the pandemic, only Taiwan has provided donations to the Daniel Ortega regime, with over 300,000 masks and 10,000 rapid tests. Despite the stalled investment in the canal, China has not granted aid to Nicaragua.

Elsewhere in Latin America, donations from China multiply as confirmed cases of COVID-19 increase.

Peru expands its investments

The Sino-Peruvian relationship is long-standing. Kevin Gallagher, author of The China Triangle: Latin America, China’s Boom, and the Fate of the Washington Consensus, sees Peru as one of China’s essential suppliers of copper. And in addition, Peru signed a Free Trade Agreement with China on April 28, 2009. Now, at a time of crisis, the relationship appears to have been consolidated further.

Including public and private donations from China, Peru’s healthcare entities have received approximately half a million masks to date. 100,000 alone came from AliBaba, the private Chinese group belonging to Jack Ma, which also donated 20,000 molecular tests and five mechanical respirators, one of the most vital pieces of equipment to treat people affected with the virus.

Elsewhere, Huawei Peru purchased over 200,000 masks to donate to the Peruvian health authorities, along with medical equipment such as gloves and protective glasses. “Guided by our sense of responsibility, we are cooperating across our countries of operation,” emphasized Huawei Peru’s chief executive Bao Getang.

Huawei’s donation is by no means trivial. Just over a year ago, Peru’s Minister of Economy Carlos Oliva announced the establishment of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to attract foreign investment. Among the potential investors was Huawei, one of the largest companies in China. “This is a huge plan,” said Oliva, given that the investment totaled close to $3bn.

Another similar case relates to a donation made by the China Three Gorges Corporation and Yangtze Power company on May 17, consisting of 46 monitors, 36 defibrillators, 25 ventilators, and 18 Doppler ultrasound scanners. Critics asked why a foreign company would make such a generous donation. The answer could lie in the purchase of Peru’s largest power distributor, Luz del Sur by the same company a year before.

Among China’s public sector donations to Peru is one from the city of Zhongshan in Guangdong province that included 200,000 masks and 100 thermometers. The donation was carried out through bilateral cooperation by diplomatic missions on both sides.

To make up for a shortfall in mechanical respirators, Peru purchased 400 from China at the end of June at a net price of $1.26m, or five times the total value of donations. And that is just on respirators. Prior to this, 700,000 rapid tests for COVID-19 were purchased from Chinese pharmaceutical company Orient Gene Biotech, but it soon became evident that they lacked any official certification.

China sets sights on Colombia

According to the Center for China Studies in Bogotá, the Chinese community in Colombia had reached 10,000 inhabitants by 2008, a relatively small group compared to others such as those of Peru or Venezuela. Over the past 12 years however, the number has increased to approximately 25,000, along with scope of investments and relations between the two countries.

“Colombia is only recently looking to China,” says Dr. Martha Ardila. “Unlike other countries such as Mexico, Peru, or Chile, which are also part of the Pacific Alliance, Colombia lags behind. But in the government of Juan Manuel Santos, and later that of President Iván Duque, bilateral relations have developed significantly”.

Colombian imports from China increased substantially from 1992 to 2020, its foreign trade with China increasing from just over $227,000 in imports in the 1990s to almost $549.7m in 2020 according to statistics from the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism.

Other signs of how the relationship has developed in recent years include school scholarships, joint infrastructure projects such as the Mar 2 highway, and technology cooperation, including investments made by Huawei. With the arrival of COVID-19, there have been large donations from China. “Although the project is currently on hold, there was even talk of a direct flight between Bogotá and Shanghai,” says Ardila. Understandably, the pandemic has grounded these plans for the time being.

On March 26 China’s ambassador to Colombia Lan Hu pledged a donation of 100,000 face masks along with virus detection reagents used in test kits. A further shipment of biosafety material, respirators, and diagnostic tests was announced for May 7, including 30,000 screening tests, 680,000 face masks, goggles, protective gloves, infrared thermometers, and respirators.

“It is an honor to receive this important donation (…) We have confronted this epidemic under the control and command of President Iván Duque with the support of all cabinet ministers,” a statement by Colombia’s Minister of Health and Social Protection, Fernando Ruiz Gomez declared. According to ministry sources, the donation had an approximate value of $1.5m.

A few days after reporting defects in over 50,000 COVID-19 tests purchased from a Chinese company at the end of April, Colombia bought a further half million Chinese kits.

An investigation by the Latin American Network of Journalists for Transparency and Anti-Corruption (PALTA) revealed that Colombia had also made three orders of rapid tests from Chinese laboratories Hightop Biotech and Biotest Biotech, neither of which were certified by China’s National Administration of Medical Products. “The Hightop Biotech tests were sold by local suppliers Bio Diagnosticos to the Departmental Hospital of Nariño in the west of Colombia and by Labtronics to the Municipality of Montería in the north. These purchases were in excess of $5,000 and $31,900, respectively. The Biotest Biotech tests, meanwhile, were supplied by local provider Ingsulab to Bogota’s Santa Matilde de Madrid Hospital for $204”, stated PALTA.

Ardila believes that the Chinese government is taking advantage of the situation for two main reasons. The lack of preparation by Latin American states, and the power vacuum that the US has left in the region.

“Trump’s behavior has left much to be desired, and nowhere more so than in Latin America. China is making the most of this, but all humanitarian aid comes at a price. China will be well placed to help Latin America recover from the pandemic, as the region has been affected economically and socially”, she added.

Yet for Colombia’s political elite, the apparent lack of ideological affinity with China matters little. The 2019 visit by President Duque, a representative of the right-leaning Democratic Center party, was publicized as “a commercial milestone”, with 12 agreements signed covering a wide range of issues from legal to economic.

“There are, as it happens, China-funded Confucius Institutes in Bogotá and Medellín. There is undoubtedly a kind of cultural resistance, as Colombian culture is completely different from that of China, yet businesses are feeling increasingly confident when it comes to working with Chinese counterparts”, says Ardila. However, she warns that it would be difficult for China to overtake the US as Colombia’s main commercial and political partner, given the historical relationship built over decades of diplomatic cooperation.

“The US is the main benchmark for Colombian foreign policy. Issues such as drugs, security, trade, and migration unite them. Increasingly, we see the technological, commercial, and now health war between China and the US, which has weakened the latter’s position in the international system,” she concludes.

Donations are affected as guanxi finds it’s limited in Chile

The cultural gaps between East and West extend also to commercial and business relations. Yet there is a concept that anyone wishing to do business with China must understand. Guanxi (关系), is the Chinese practice of creating social and cultural bonds of trust in order to strengthen business and commercial relations.

Entrepreneurs, public officials, and businesses seeking to establish relationships with public or private Chinese companies usually learn about guanxi, as it can have a major impact on success. In practice, the term is represented through activities and gestures of a personal nature that seek to inspire confidence in interpersonal relationships. Politeness, together with close and long-lasting relationships, are all aspects that combine to improve guanxi.

This helps us to understand what is happening with Sino-Chilean negotiations. “It is not just about corporate social responsibility, which is what you might think would be the case with well-resourced companies like these. They do not look to simply appear ‘nice’. The Chinese conduct themselves through guanxi, and the set of sound relationships and quality contacts that allow the development of networks that promote their interests. When you look at it this way, the Chinese are not simply donating, they are investing,” considers Von Wolff.

China has not advanced as prominently in Chile as it has in other countries in the region. What has been a success however is the support provided by Chinese companies on Chilean soil. On April 28, the Zhejiang Chamber of Commerce in Chile donated 50,000 masks, 600 face shields and a “sanitation tunnel” to the Investigations Police of Chile, the country’s civilian police force.

“We consider Chile our second home, and the members of the Investigations Police, its national heroes. We therefore want to ensure the health and safety of each of you, to establish a first line of defense during this pandemic” said Chen Wenguang, the Chamber’s president.

It is worth noting that in 2017 China’s biggest domestic wine producer, Changyu Pioneer Wine, acquired an 85% stake in Bethwines, one of Chile’s largest. It is perhaps not surprising therefore that when the COVID-19 crisis hit, Chilean diplomats turned to China.

Referring to his “friend” the chairman of Changyu, Chile’s ambassador to Beijing Luis Schmidt said, “When I called to tell him we were going through challenging times, he said: ‘Ah, but immediately’. He then offered me a valuable donation of essential resources”. This was stated in an interview with Chilean daily La Tercera, but despite the reporter’s insistence, he never revealed what the donation consisted of.

During the same interview, Schmidt listed other companies that have made donations to Chile, including Tianqi Lithium, China Construction Bank, and Joyvio, which in November 2018 bought Australis Seafood, a major Chilean salmon business. “Many companies have collaborated strongly. We are really happy,” he said. He also treated the director and chief executive of Tianqi at the time, Vivian Wu, as a “very good friend”.

Speaking in an interview with the same newspaper, China’s ambassador to Chile, Xu Bu, announced that Tianqui Lithium planned to donate 200,000 medical masks, 30,000 tests and 10 ventilators to Chile. “The China International Development Cooperation Agency, the people’s governments of Sichuan Province, the cities of Chengdu, Shenzhen, and Ningbo, as well as China Minmetals Corporation and the Bank of China in Chile, among others, have all pledged to donate medical supplies. People from Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces living in Chile have also made donations. We are in contact with the relevant Chilean authorities to coordinate the delivery and transportation of the donated supplies,” said Xu Bu.

In reference to Tianqi, British consulting firm Roskill indicates that due to the pandemic, lithium production in Chile is expected to decrease by 20%, which could translate into losses of $960m. In 2010 the company bought a 23.77% stake in SQM, the listed Chilean chemical group, for a value of $4.07bn, the largest transaction that a company has made in Chile.

“China is our main commercial partner, and a major investor. But these donations are eventually paid for in various ways. It almost ends up being more expensive than buying the supplies outright. Relatively speaking, we are better off than other countries, and we can secure supplies without having to resort to donations,” says Von Wolff, pointing out that China’s other interest in Chile is the copper market.

This, of course, does not sit comfortably with the US. Since his 2019 visit to Santiago, Mike Pompeo has warned Chile to be careful about its relationship with China, while the Chilean position is to treat each relationship separately.

What is even more evident is the faith Ambassador Schmidt places in a possible Chinese vaccine. “There are currently eight or nine vaccines around the world that are more advanced, but China has five that are even more so than in US, British or German laboratories,” he says, indicating that Beijing is interested in Chile being the main vaccine supplier for Latin America.

Brazil and China, partners despite the circumstances

“Once again, we see a dictatorship that prefers to hide something serious than expose it and risk triggering a political crisis that could otherwise save lives. China is to blame, and freedom is the solution,” said Eduardo Bolsonaro, a member of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies and son of President Jair Bolsonaro, on March 19. While the media presumed this would trigger a diplomatic crisis, the President himself quickly dismissed the comment.

A month later, Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court authorized an investigation against the Minister of Education at the time, Abraham Weintraub, for alleged anti-Chinese comments. Weintraub had published an illustration on social media where the letter “R” had been changed to an “L”, alluding to popular stereotypes of how Chinese people speak.

The truth is that while members of the Bolsonaro cabinet publicly criticize the Chinese government and blame it for the pandemic, China’s “mask diplomacy” is clearly not affected by words alone as it reaches South America’s largest economy.

It is important however to understand the wider context. The relationship between Brazil and China intensified under the social democratic government of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who in 2004 took no fewer than 400 Brazilian businessmen to China to establish investment and trade agreements. The result: China has been Brazil’s main trading partner since 2009.

At the other end of the political spectrum, Bolsonaro reasserted this position during his 2019 visit to China, a country with which Brazil achieved a trade flow of $98.9bn in 2018. Declared Chinese investment into Brazil reached $102.5bn between 2007 and 2018, 56% of which has been confirmed, according to an investigation by the China-Brazil Business Council. During the same period, 145 projects were carried out in Brazil, equal to almost half of all investments registered across Latin America and the Caribbean.

“I was looking forward to this visit, as China is now our main business partner, and I am looking forward to strengthening this business and to broadening our horizons. Today we can say that a significant part of Brazil needs China,” said the Brazilian president during his meeting with Xi Jinping, despite previously accusing China of wanting to “buy Brazil.”

Both countries went on to sign no fewer than 25 agreements covering policy, science, technology, education, economy, trade, energy, and agriculture during the 2019 visit, as reported by the national public service news agency Agência Brasil. Foreign Affairs magazine has referred to Sino-Brazilian relations as a “marriage of convenience”.

Amid the criticism and COVID-19, Chinese donations have entered Brazil in earnest. The approximate value of donations is around $3m. Compared with the overall scale of confirmed investments, this does not seem like much.

In July, China’s ambassador to Brazil, Yang Wanming, indicated that bilateral cooperation on infrastructure projects was still under way, and that much of China’s $80bn investments in Brazil was destined for this sector.

“Chinese companies are closely following specific projects in this sector and are optimistic about the long-term investment prospects in Brazil. They are willing to intensify and streamline communications in order to establish a model of cooperation that meets expectations on both sides,” said Ambassador Yang.

Argentina and China united

In Argentina, an ordinary shipment of donations of medical supplies arrived from China on April 14, but the boxes that contained them were unusual. A famous quote from 19th Century Argentine poet José Hernández on the sides of the boxes read “Let brothers be united, because that is the first law. Have a true union in any time that goes,” sending an enduring message in both Chinese and Spanish.

Just as the political differences between Bolsonaro’s Brazil and the Chinese Communist Party were not enough to harm their relationship, the ideological stance of the Alberto Fernández government in Argentina has generated commercial change. Last year, for the first time, China overtook Brazil as Argentina’s largest trading partner, a trend that has become even more marked in 2020.

The pandemic has undoubtedly influenced this change. According to a report by BBC Brazil, the crisis generated by COVID-19 has slowed, and perhaps even paralyzed industry. This has been particularly apparent in the automotive sector, which represents at least 40% of trade between Brazil and Argentina. Experts believe that this could explain Argentina’s new economic direction.

Buenos Aires’ rapprochement with Beijing transcends commercial issues. There are plans to install a Chinese space observatory for missions to the Moon in the Argentine province of Neuquén, in Patagonia, and a controversial large-scale pork production agreement to supply products destined for China’s internal market.

After a meeting between government officials and representatives of the China National Biotec Group and Argentina’s Elea Laboratories, the two organizations that are working together to carry out domestic trials, the Argentine Ministry of Health announced on August 22 that China’s Sino. pharm vaccine would be tested in Argentina.

The Argentine Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship has stressed that cooperation between the two countries is diverse. “It includes subnational entities, companies, institutions and other entities that have made donations and sent supplies to various actors in our country,” it told Fundeps, the Foundation for the Development of Sustainable Policies.

In terms of economic aid, China has allocated around $4.71m to Argentina, according to data released by the Wilson Center.

Yet there have also been purchases. Buenos Aires Province imported five-and-a-half million disposable face masks from China, 300,000 N90 masks, 83,000 goggles, 700,000 face shields and 12 million pairs of disposable gloves worth $54m, according to the Argentine open-access platform Chequeado. To achieve this, national carrier Aerolineas Argentinas carried out 32 flights to Shanghai at a cost of $500,000 each, according to the site.

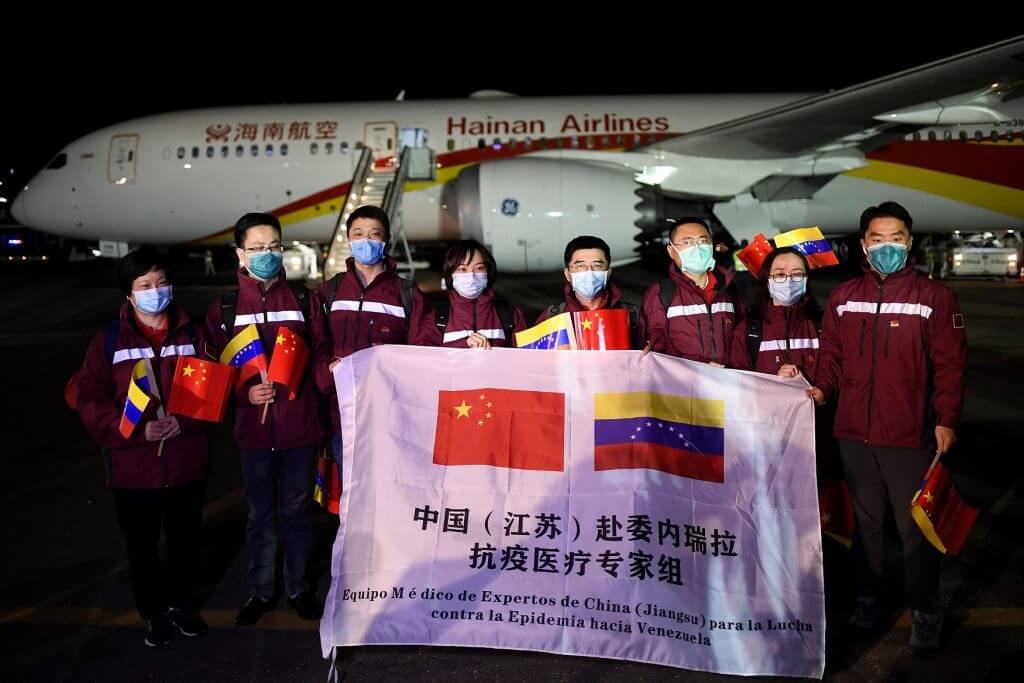

Venezuela and China, “automatic solidarity”

In Venezuela, COVID-19 hit at a time when the country was already going through a complex humanitarian crisis and suffering a collapsed economy. Armed with a message of brotherhood and solidarity, China has emerged as the savior of Venezuela during the pandemic, providing the country with millions of dollars’ worth of donations.

This is not a new phenomenon. Over the last ten years, Venezuela has received the most amount of money from China in Latin America. An investigation carried out by the Venezuelan chapter of anti-corruption network Transparency International calculated that Venezuela has received $68.68bnfrom China, of which 91.2% was in the form of loans. “$50.24bn was received through the China-Venezuelan Joint Fund and Large Volume Long Term Fund alone, of which more than $16.73bn was outstanding by end-2019, a figure three times that of Venezuela’s international reserves for March 2020,” revealed a report by Transparency Venezuela entitled simply Chinese Business. It is believed that these agreements have served to undermine democracy in Venezuela.

When China needed a large supply of oil, it found it in the Venezuela of late president Hugo Chávez. “During those first years, both governments appeared to profit from such cooperation, but the death of Chávez changed things radically,” Matt Ferchen, an academic at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy told BBC Mundo.

The benefit for China was measured by propaganda and the growth of its presence in the region. “Chávez’ expansionist policies gave China the opportunity to extend its economic reach in Latin America. Venezuela became a mouthpiece for Chinese policies in the region, which was China’s main interest during the oil boom,” states Parsifal D’ Sola.

Oil prices then fell, and economic restrictions continued, leading to an unprecedented socio- political crisis. Venezuela saw the highest levels of inflation in the world and now has serious problems with the supply of basic products such as medicine, food, gasoline, water, and electricity.

Yet the relationship between China and Venezuela has not been entirely satisfactory for the larger of the two partners. “It was clear during the last visit of President Nicolás Maduro to China in 2018 that the relationship had already started to cool. What would have previously been hailed as an important occasion went completely under the radar”, indicates D`Sola.

The crisis, together with poor management by the Maduro government meant that Caracas has failed to fulfil some of its agreements with Beijing, leading to requests for “grace periods” and the accompanying—and unwelcome—publicity of being a partner to a country in ruins.

“With Venezuela, everything has been a disaster. Little by little, the Chinese have recovered their money, but the hope that Venezuela would serve as an example to the region of what a country could become with China’s help has disappeared,” says D’Sola.

Because of the practical nature of being an ally to such an unstable country, China has directed a large amount of aid to Venezuela during the pandemic. The message has been clear: support is based on the solidarity and brotherhood that unites them.

Only six days after the confirmation of the first cases of COVID-19 were observed, 55 tons of medical supplies arrived in Venezuela as part of their joint cooperation agreements.

To date, Venezuela has received 1,745,160 tests, 6,633,000 masks, four ventilators, approximately 30,000 doses of chloroquine, 70,000 infrared thermometers, 8 medical specialists, and 100,000 protective suits and gloves, according to Wilson Center data. This equates to a total donation of $14.82m excluding medical professionals, representing 4% of all COVID-19 donations made by China to Latin America.

China acts with a kind of “automatic solidarity,” former Venezuelan ambassador to the United Nations, Milos Alcalay told Voice of America’s Spanish news service, VOA Noticias. “China is playing for high stakes, as it had managed to maintain institutional relations with all sectors,” he notes.

As D’Sola points out, this, including the extensive COVID-19 donations, serves to obscure long-term economic interest. China will be looking to “break new ground” for future investments of its companies in the continent.

New geopolitics, new normal

With China expanding its reach through mask—and vaccine—diplomacy, the US tied up with its own domestic politics, and a pandemic raging in weaker economies such as those found in Latin America, we may get a glimpse of how the bankruptcies of countries in Latin America and elsewhere will be worked in China’s favor, believes Evan Ellis.

“An economic crisis in Latin America would allow Chinese companies to buy up operations in the region, which would happen especially if they are sold cheaply and coincide with depressed commodity prices. These low prices also give China significant leverage when negotiating with governments in the region,” says Ellis.

Before the arrival of a pandemic that has claimed over a million lives worldwide, access to markets in poor states was through direct credit. Large loans were typically negotiated between Beijing and the country that was struggling financially. Interest rates were generally high, and the influx of money allowed them to escape financial turmoil. Yet the one element that was most often overlooked was the most important: the fine print.

In the event of a default, these hidden clauses could eventually make it easier for China to take over strategic sectors, although there is no evidence of this to date. In Venezuela, it is oil, which is now highly leveraged. Each country has something tempting to offer. Ports, gas, nuclear plants, hydroelectric power, waterways, railways, crude oil, mining. Not to mention a consumer market of 33 Latin-American economies and over 650 million people.

Translated by Edward Longhurst-Pierce