Strategic Diversification and Human Rights: Challenges for Colombia in Its Commercial Approach to China

Colombia faces a strategic dilemma in diversifying its trade relations towards countries like China due to recent tensions with the United States (U.S.) under the Trump and Petro administrations. While the Belt and Road Initiative offers opportunities in investment and infrastructure without political conditions, it also presents significant challenges in human rights, an area where the U.S. has historically conditioned its economic support and bilateral cooperation. China’s divergent approach, focused on social stability and economic development, contrasts with the Western vision based on individual freedoms and democracy, potentially generating internal tensions, socio-environmental conflicts, and international scrutiny regarding Colombia’s commitment to these fundamental values. In a shifting geopolitical context, Colombia’s opening toward China must be approached with caution to avoid compromising the country’s international reputation or undermining its progress in human rights and institutional development.

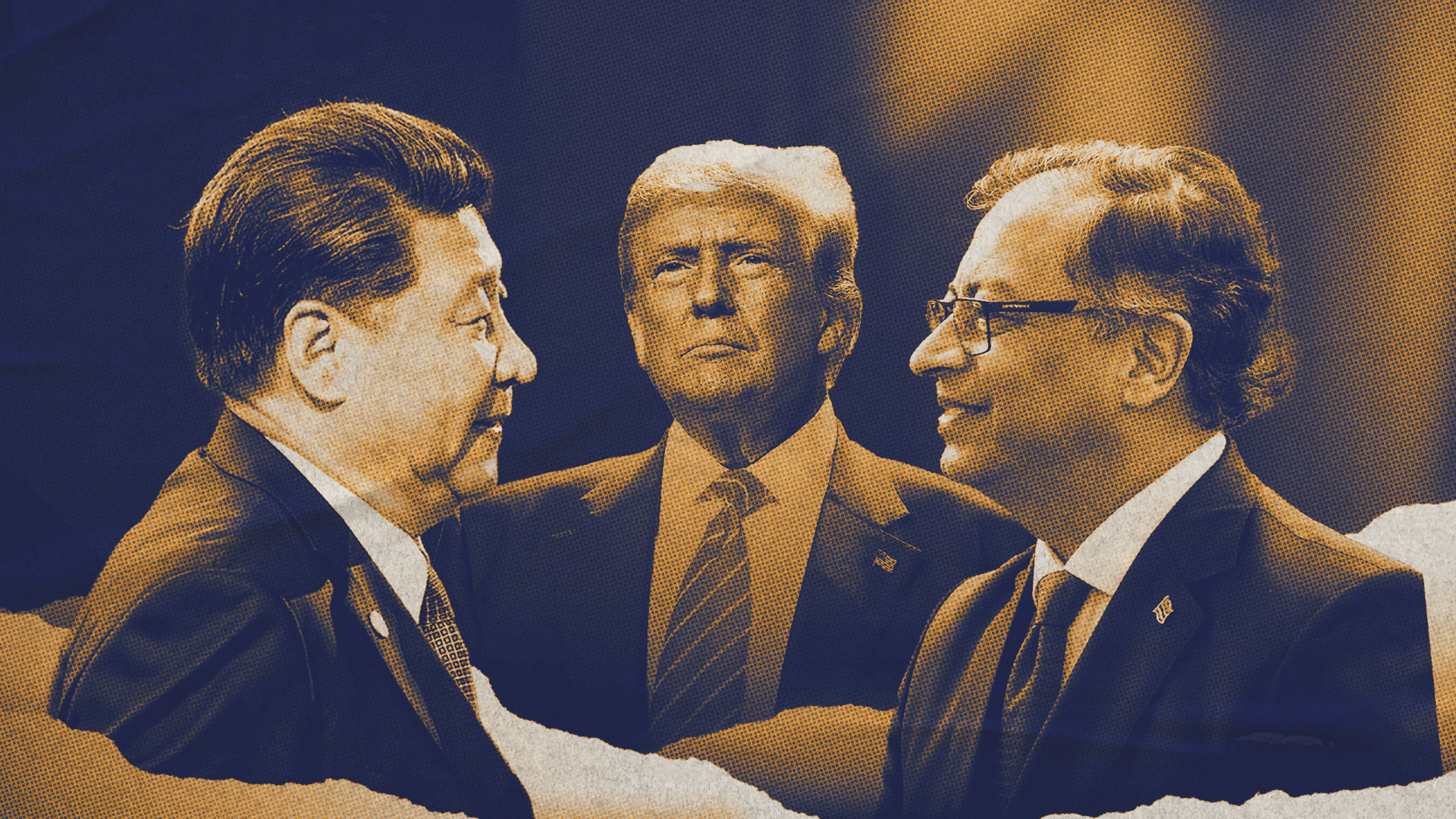

Colombia faces a complex foreign policy scenario with the United States (U.S.) due to recent tensions between presidents Donald Trump and Gustavo Petro. The historically strong bilateral relationship—characterized by trade agreements, security cooperation, and significant U.S. political influence—has been tested, prompting the Colombian government to seek new alternatives. In this context, China emerges as a potential strategic partner, offering investment, financing, and infrastructure through its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, Colombia’s market diversification towards the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is not without difficulties, especially regarding human rights—an issue that has been central to bilateral relations with the U.S. and was impacted by funding cuts under the new administration.

China offers investment, financing, and infrastructure through its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. However, this relationship is not without challenges, particularly regarding human rights.

Colombia’s trade relationship with China has grown over the past two decades, making the Asian country its second-largest trading partner after the U.S. China’s demand for raw materials such as oil, coal, and agricultural products has strengthened economic ties, while the import of Chinese technology and manufactured goods has contributed to the development of strategic sectors. Nevertheless, China’s pragmatic approach to economic cooperation does not include the human rights component that has historically underpinned Colombia-U.S. relations. While Washington has often conditioned its economic support on progress in areas such as anti-corruption efforts and democratic strengthening, China follows an economic diplomacy model that prioritizes political stability and non-interference in its partners’ internal affairs.

While the U.S. conditions its economic support on anti-corruption efforts and democracy, China prioritizes political stability and avoids intervening in internal affairs.

China’s perception of human rights differs significantly from that of the West, largely due to its historical and political context, particularly at the time of the United Nations’ (UN) creation in 1945. Back then, China’s legitimate representation before the international community lay with the nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek, an ally of the U.S., rather than the People’s Republic of China, which was proclaimed in 1949 after the Communist Party of China (CPC) won the civil war. This suggests that the human rights principles established in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights were formulated without CPC involvement or input, and once in power, the party developed a perspective beyond these principles. This perspective is rooted in the Confucian tradition, where social harmony and collective well-being take precedence over individual rights—contrasting with the Western focus on individual freedoms and fundamental liberties.

As a result, China’s human rights conception differs from that promoted by the U.S. due to its emphasis on state stability and economic development as core pillars. For China, state survival and strength are paramount, as it believes that without a strong government and a cohesive society, individual rights cannot be effectively guaranteed. This perspective has led the Chinese government to justify the subordination of civil and political rights to broader development and stability objectives, endorsing restrictive policies in the name of economic progress and national unity. In contrast, the U.S. has advocated for a human rights approach centered on individual protection, democracy, and political freedoms, leading to recurring tensions in international human rights forums. China, for its part, maintains that economic development and poverty eradication should be considered fundamental human rights, whereas the West places greater emphasis on freedom of expression and political participation as essential components of these rights.

China’s vision of human rights emphasizes social harmony and collective well-being, in clear contrast to the Western perspective, which is centered on the individual.

China’s model, based on social stability and economic development as fundamental pillars, clashes with the Western vision of human rights, which prioritizes individual freedom and democracy. Under this premise, China has faced international criticism for its restrictions on freedom of expression, repression in Xinjiang, and governmental control over civil society. For Colombia, whose democratic system has evolved within a framework of guarantees and citizen participation, closer ties with China could generate tensions both domestically and in its relations with other Western allies. Colombia’s potential adhesion to the Belt and Road Initiative could bring benefits in infrastructure and trade, but it would not replace the financial support that the U.S. has provided through human rights initiatives, institutional strengthening, and assistance to vulnerable communities—dynamics closely linked to the country’s complex security situation, marked by illegal armed groups operating in ungoverned territories for over 50 years.

Colombia’s challenges in diversifying its relations with China in terms of human rights stem, in part, from China’s political system itself. While the U.S. and the European Union have promoted cooperation policies with Colombia in exchange for commitments to transparency, accountability, and access to justice, China does not condition its investments on these factors. This means that while the Colombian government could receive funding and trade agreements with fewer political requirements, it could also face greater pressure from international organizations and civil society, which might see this engagement as a weakening of human and environmental rights protections.

Closer ties with China could generate internal tensions and raise concerns among Western allies about Colombia’s commitment to democracy and human rights.

Another key challenge lies in Colombia’s international credibility. Aligning with China or another authoritarian state without a clear strategy to balance relations with the U.S. and Europe could affect Colombia’s image in multilateral forums and its negotiating capacity in trade and cooperation agreements. Colombia has been a relevant actor in human rights advocacy in Latin America and has received support from various international organizations for implementing the Peace Agreement and protecting social leaders. A drastic shift in its foreign policy could be interpreted as a retreat from these commitments, undermining international trust and limiting access to funds for social and sustainable development programs.

The weight of U.S. human rights cooperation is significant. Through initiatives such as Plan Colombia and State Department assistance, the U.S. has allocated billions of dollars to strengthen institutions, security, and respect for fundamental rights in the country. According to the Colombia-U.S. Chamber of Commerce, approximately USD $401 million was allocated in 2024 for humanitarian assistance, anti-narcotics efforts, and armed forces support. This cooperation has also been crucial for protecting vulnerable populations and promoting judicial reforms within the National Human Rights Plan. In contrast, Colombia’s relationship with China has been based on an investment model without political conditions—an attractive economic approach, but one that does not ensure the same level of support for first-generation rights: life, freedom, integrity, and security.

U.S. cooperation on human rights has been crucial for Colombia. In 2024 alone, it allocated $401 million to humanitarian assistance and the fight against drug trafficking.

Engagement with China also presents internal challenges, as Beijing’s development model does not necessarily align with the Colombian government’s social and environmental priorities. The expansion of large-scale infrastructure projects without proper prior consultation with Indigenous and rural communities could spark social conflicts and raise concerns about the state’s commitment to collective rights. Additionally, dependence on commodity exports to China risks perpetuating an extractivist economic model with negative environmental impacts and limited diversification of Colombia’s productive sectors.

Despite these challenges, economic diversification remains a priority for Colombia—at least for the current administration. Dependence on a single trading partner is risky in a volatile global economy and amidst fluctuating political relations, particularly given the tensions reflected in the February 26 exchanges on X between Washington and Bogotá.

China offers opportunities in strategic sectors such as technology, renewable energy, and infrastructure, but Colombia must approach this relationship cautiously, ensuring that its pursuit of new markets does not entail concessions on human rights or commitments that weaken its international reputation—one already scrutinized over the past 25 years due to human rights violations and the government’s inability to effectively guarantee them.

Colombia faces the challenge of diversifying its international relations without compromising its global credibility or weakening progress on human rights.

Colombia’s diversification of international relations, particularly its engagement with the PRC, could mark a turning point in its foreign policy, challenging its historical dependence on the U.S. However, this strategic shift is not without tensions, especially in the human rights domain, where competing models are evident. In a world transitioning to multipolarity, Colombia must act cautiously to ensure its market diversification does not erode its human rights progress or weaken its global standing in an evolving international system.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES

- La suspensión de ayudas de cooperación de Estados Unidos amenaza la supervivencia de las ONG en Colombia

- Perspectivas actuales para el estudio de los derechos humanos desde sus dimensiones

- Algunas ideas en la cultura china tradicional relacionadas con la Concepción de los Derechos Humano: con especial atención a las obras de Mencio

- People Power and Ethnic Forces in Myanmar’s Spring Revolution: The Responsibility to Protect

- CHINA: perspectivas de política exterior en la post Guerra Fría

- Colombia es el mayor receptor de ayudas de Estados Unidos en los últimos 50 años