The China-CELAC Forum: All Optics, No Strategy

The 4th China–CELAC Ministerial Forum underscored the persistent asymmetry in China–Latin America relations. Despite broad participation from regional leaders, the event was marked by symbolic rhetoric and a lack of concrete outcomes. Colombia’s signing of a cooperation plan under the Belt and Road Initiative highlighted diplomatic improvisation and the absence of a clear foreign policy strategy—standing in contrast to the technical preparation of countries like Brazil and Chile. The article argues that the core issue lies not only in the forum’s design but also in the region’s internal limitations in articulating a coherent and strategic global voice.

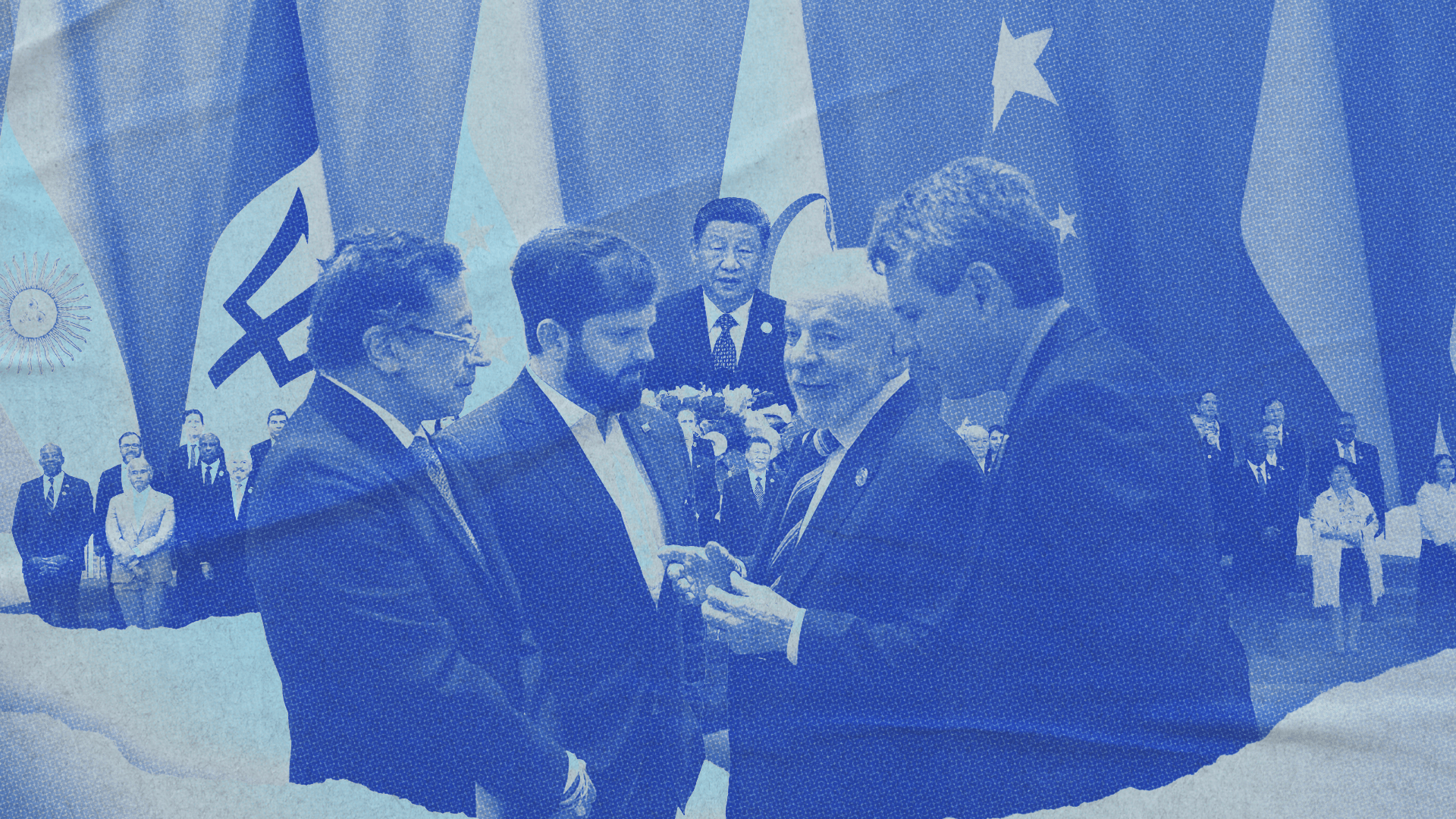

The celebration of the 4th China-CELAC Ministerial Forum in Beijing did not mark a strategic shift in the relationship between Latin America and China. On the contrary, it once again exposed a fragmented region, a growing imbalance in the face of Beijing’s carefully crafted global narrative, and a meeting format filled with symbolic gestures but lacking tangible outcomes. Despite broad participation—17 foreign ministers and three heads of state, including Gustavo Petro, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and Gabriel Boric—the forum once again emerged as an exercise in rhetorical diplomacy with no solid operational structure.

“The forum once again emerged as an exercise in rhetorical diplomacy with no solid operational structure.”

One of the most striking gestures was Colombia’s signing of a cooperation plan under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). For China, this represents a significant diplomatic victory: it succeeded in associating one of the United States’ traditional allies in the region with President Xi Jinping’s flagship global initiative. However, the decision appears to have been more of a domestic political tool for President Gustavo Petro than the result of a coherent foreign policy strategy. The public undermining of his foreign minister, Laura Sarabia, prior to the trip, underscored the lack of alignment and coordination within the Colombian government.

Moreover, the memorandum signed with Beijing fits the generic template of agreements that China has signed with dozens of countries: cooperation in connectivity, health, technology, trade, and sustainable development—but without concrete projects or clear priorities. This ambiguity places Colombia in a passive position, where China will set the pace and scope of the relationship.

Petro, however, described the agreement as a “flexible collaboration platform” that would allow Colombia to assess “each project individually” and its impact on the local population. With this statement, the Colombian government seems to be seeking a more pragmatic model, similar to that of Brazil, which has not formally adhered to the BRI but works on establishing specific synergies between the initiative and its national development strategies. The difference lies in the degree of planning: while Brazil arrives with roadmaps, Colombia improvises under political pressure.

“Colombia improvises out of political urgency, while other countries arrive with clear roadmaps.”

Beyond the content, Petro appeared to use the occasion to project a symbolic international victory at a time of growing domestic challenges. The BRI adhesion provided an easily communicable diplomatic win, albeit one difficult to materialize. In line with his aspiration to position himself as a regional leader on the global stage—an ambition pursued with clumsiness and contradictions—Petro even proposed a CELAC-U.S. summit during his speech, attempting to balance his approach to China with a conciliatory narrative toward Washington. This caution, however, reinforces the idea that there was no prior diplomatic groundwork with either China or the United States. Colombia lacks both a clear foreign policy toward Beijing and a defined strategy for its principal historical ally.

Further evidence of this disarray came from outside the forum: Petro formally requested Colombia’s entry into the BRICS bank. That this request did not take place within the framework of the multilateral event reaffirms a key point—the most practical and substantive advances are achieved through well-structured bilateral negotiations, not in multilateral forums like China-CELAC. Other countries illustrated this lesson clearly. Brazil, with a delegation of nine ministers, and Chile, with well-defined goals, used the forum as a platform to advance their own agendas. The comparison is stark: some arrive with technical preparation, while others, like Colombia, come without a roadmap and get trapped in vague promises that serve China’s narrative more than their own interests.

“Practical and substantive progress is not achieved in spaces like the China-CELAC forum, but through well-structured bilateral negotiations.”

Beijing, for its part, presented a well-articulated speech and meticulously projected leadership. Xi Jinping outlined five major cooperation programs—political solidarity, economic development, civilizational exchanges, shared security, and people-to-people connectivity—accompanied by flashy numbers and grandiose concepts such as a “community with a shared future.” However, this display lacked verifiable mechanisms and concrete commitments. For instance, the announced $9.2 billion credit line came without details on timelines, conditions, or criteria. Even more revealing: this amount is less than half of the $20 billion China pledged at the 3rd Ministerial Forum in 2015. For a region of over 600 million people, the sum is practically insignificant—especially when compared to Africa.

Indeed, the contrast with China’s engagement in the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) is telling. In the 2025–2027 action plan, China promises $50 billion to Africa over the next three years, including credit lines, direct aid, and corporate investment. This quantitative and qualitative gap suggests that Beijing views CELAC as a weak and informal platform, lacking binding legal structures and enforcement mechanisms.

Ultimately, the 4th China-CELAC Forum did not transform the relationship—it confirmed it: China continues to set the terms, the language, and the pace of engagement, while Latin America responds in a fragmented way, with little technical preparation and scant strategic clarity. In this imbalance, the risk is not only that the region adopts China’s agenda, but that it does so without first defining its own interests. By embracing Beijing’s proposed language—with expressions such as “civilizational exchange,” “community with a shared future,” or “South-South solidarity”—Latin American governments risk subscribing to a conceptual framework they did not help construct and that may not align with their true development priorities.

“Neither rhetorical victimhood nor multilateral symbolism can replace effective foreign policy.”

The regional left often insists that the voices of Latin America and the Caribbean are not heard in global forums, and that their interests are systematically ignored. But if the China-CELAC forum made anything clear, it is that the problem may not lie solely in the design of the international order, but in deeper internal shortcomings: lack of coordination between countries, low technical capacity, improvised diplomacy, and insufficient professionalism. In a global scenario that demands strategic clarity and negotiation skills, rhetorical victimhood and multilateral symbolism are no substitutes for an effective foreign policy.