The changing phase of China’s lending practices in Latin America and the Caribbean

Ilustration by: Alonso Gañan.

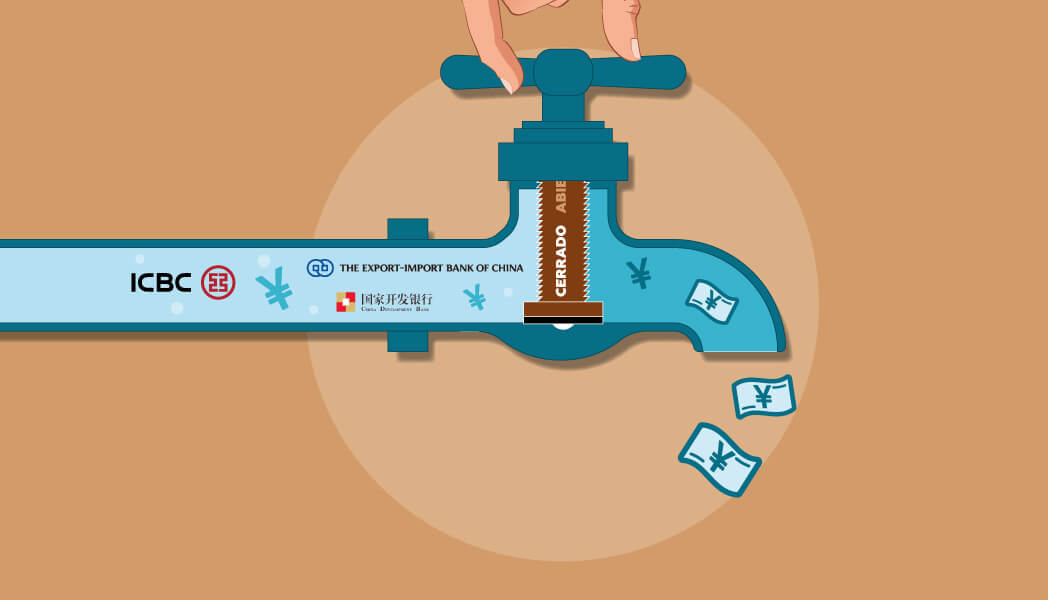

It is plausible that 2020 marked an inflection point in China’s relationship with Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). According to joint research between Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center and the Inter-American Dialogue, last year was the first time, since 2006, that Chinese policy banks did not extend new loans to LAC governments. This comes after China stood as the major creditor of the region for more than a decade. China’s financing in LAC has been on the downside since 2017, dropping from $6.3 billion to $2.1 billion in 2018, to $1.1 billion in 2019, and to zero in 2020. The absence of new loans does not mean that China is disengaging from the region, on the contrary, an increase in direct investment and a growing focus on trade hint at a shift in kind, not in degree, regarding Chinese participation in the region.

China’s lending practices in the Global South have long been subject to intense debate and controversy, especially in the context of the growing tensions between Washington and Beijing. Many critics ascertain that China intentionally pursues “debt-trap diplomacy,” which refers to cajoling developing countries into taking loans for expensive projects they cannot afford, all with the end goal of taking control of valuable assets in said countries. On the other hand, some analysts emphasize that China is simply filling a gap in infrastructure financing left by traditional multilateral institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, arguing that concerns about unfair terms and loss of sovereignty are greatly exaggerated.

Regardless of the intensity of the debate, the truth remains that most of it is based on conjecture. Of the more than 2000 financing contracts that China has signed with countries around the globe, only a fraction of them have been made public, which makes any kind of assessment of Chinese financing limited at best. Most research and discussion on the topic rests upon anecdotal accounts in media reports, cherry-picked cases, and excerpts from a small number of contracts. Furthermore, there is little to no evidence that China has relied on debt burden to acquire assets in any country, as research from Johns Hopkins University and the Rhodium Group have highlighted on multiple occasions. The controversy surrounding Chinese financing is hence more a manifestation of geopolitics than a genuine debate on China’s financing mechanisms.

Notwithstanding, it is the lack of information on Chinese lending that is the root of all criticism. This March, the research lab AidData published the first-ever systematic analysis of the legal terms of China’s foreign lending. They collected and analyzed 100 contracts between Chinese state-owned entities and government borrowers in 24 developing countries, including eight from LAC. The study draws three main insights. First, the contracts contain rare confidentiality clauses that prohibit borrowers from disclosing the terms or even the existence of the debt. Second, Chinese lenders seek an advantage over other creditors, using collateral arrangements such as lender-controlled revenue accounts and promises to keep the debt out of collective restructuring. And third, cancellation, acceleration, and stabilization clauses in contracts potentially allow the lenders to influence debtors’ domestic and foreign policies.

It can be argued that these insights are partly responsible for the steady decline of Chinese loans in LAC. Most Chinese lending contracts are signed on a government-to-government basis, which, in conjunction with the high levels of confidentiality of the contracts, can constrain the financial maneuverability of future administrations, generating tensions with Beijing in the process. This is particularly relevant in LAC, given the often-contrasting politics of incumbents and opposition forces and Beijing’s obliviousness towards local politics.

Fifteen years ago, the so-called “pink tide”, the turn towards let-wing governments in LAC, was in full throttle and China was fueling the commodity boom that generated an unprecedented influx of capital into the region. It is around this time that China became the region’s most important creditor. Today, the political landscape is completely different, particularly with regards to Venezuela and its all-encompassing crisis. Venezuela was supposed to be the beacon of Chinese cooperation in LAC. Instead, it emerged highly indebted to China with little to show for after more than USD 60 billion in loans. State-to-state obscure dealings without legislative or public oversight is largely responsible for the catastrophic results obtained in Venezuela. Odds are that other governments in the region took notice.

Chinese authorities have probably grown aware of the political vicissitudes of LAC when extending vast long-term loans to countries in the region. The drop in Chinese financing can therefore be attributed to Chinese banks re-evaluating their lending practices, especially after the fiasco in Venezuela. The trend has been accompanied by an increase in debt renegotiations as well, Ecuador being a high-profile case, which in late 2020 renegotiated part of its debt with both the China Development Bank and the China Eximbank. Likewise, many Latin American countries have gained experience on how to deal with Chinese banks and, perhaps, have come to understand that these loans do come with strings attached, unlike China’s official portrayal of its financing mechanisms as “non-interventionist.” Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic will have lasting effects on the development of large-scale projects financed by Chinese capital.

Chinese loans aside, China-LAC trade remained steady in 2020. This is quite revealing, especially considering that LAC GDP fell by over seven percent in 2020, with exports decreasing overall. LAC’s exports to China rose slightly from $135.2 billion to an estimated $135.6 billion, while China’s exports to LAC fell slightly from $161.3 billion to an estimated $160.0 billion. Since the regions GDP fell sharply, this means that exports to China rose significantly as a share of GDP.

Another bright spot in China-LAC relations in 2020 was in the field of foreign direct investment. Chinese mergers and acquisitions (M&A) deals in the region rebounded from $4.3 billion in 2019 to $7 billion in 2020. This trend stems from Western investors selling their assets to Chinese buyers, particularly in the electricity infrastructure sector. For example, China Three Gorges Corp bought Sempra Energy’s 83.6 percent stake in Peru’s Luz del Sur, the largest electric company in Peru, for $4.1 billion, and State Grid Corp of China bought Chilquinta Energia, the third-largest distributor in Chile, from Sempra Energy’s for $2.4 billion. With both sales, Sempra Energy, one of the largest energy infrastructure companies in the United States, marks its exit from South America.

Over the last decade Chinese companies, private and public, gained important ground in LAC, with China’s policy banks and their vast loans playing a fundamental role in the process. Nonetheless, Sino-Latin American relations are probably in for an overhaul, with the pandemic serving as the catalyst. There will be new developments in “greenfield” projects, meaning the acquisition of, or merger with, existing projects. Bilateral trade will continue its course, with 2021 probably seeing a surge as countries begin to get the pandemic under control. Likewise, greater Chinese participation in the medical and pharmaceutical industries will probably stem from cooperation regarding the pandemic, given the fact that China has been active in clinical trials and vaccine production in the region. Overall, the drop in Chinese financing to LAC represents an evolving relationship, not a cooling one.