Chinese Companies and Socio-Environmental Impacts in the Andean Region: A Shared Responsibility

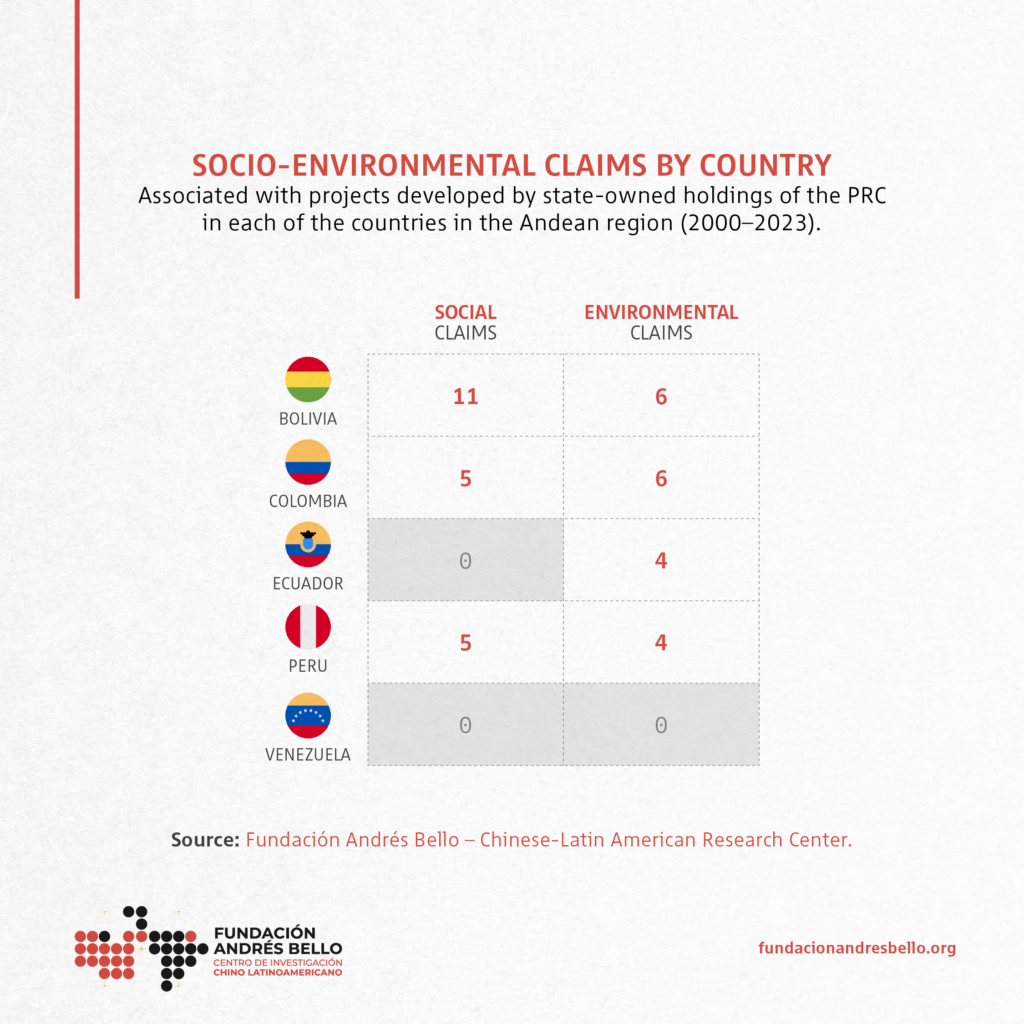

The study conducted by the Fundación Andrés Bello on the participation of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the Andean region (2000–2023) reveals that a significant proportion of projects developed in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela have faced irregularities, with approximately 15% of cases linked to social and environmental claims. The analyzed projects span sectors such as natural resource extraction and infrastructure, with recurrent issues including violations of indigenous community rights, failure to implement prior consultation mechanisms, and direct impacts on the living conditions of local populations. Environmentally, reported cases involve soil and water contamination, deforestation, damage to protected areas, and the execution of projects without required environmental permits.

This analysis emphasizes the shared responsibility between regional governments and Chinese companies, highlighting the need to strengthen institutional mechanisms in Andean countries to protect community rights and safeguard the environment. It also underscores the necessity for greater commitment from Chinese companies to implement the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. While companies are not required to guarantee rights, they must operate in ways that respect them and minimize socio-environmental impacts. Achieving mutually beneficial relationships between Chinese investments and the region’s countries requires coordinated efforts, where both states and companies effectively fulfill their responsibilities.

The study conducted by the Andrés Bello Foundation, Identification and Monitoring of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises in the Andean Region (2000–2023), revealed that 13 out of 20 projects undertaken by Chinese state-owned enterprises in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela exhibited some form of irregularity, with approximately 15% of these involving social and environmental claims. Although the study is ongoing, with a new phase of updates and expansions set to be published in November 2025, it has highlighted several trends underscoring the shared responsibility between Chinese companies and the national and/or local authorities of the countries in the region.

An analysis of the claims associated with the execution of these projects, carried out in both extractive and infrastructure sectors, reveals two major social dimensions. On one hand, there are violations of the rights of Indigenous peoples—a critical issue in a region characterized by the multicultural and multiethnic nature of its societies. On the other hand, there are impacts on the broader communities inhabiting the areas where these projects are developed. Regarding environmental claims, the most recurrent issues include soil and water contamination, deforestation and damage to protected areas, and the initiation of projects without the necessary environmental permits.

“Social claims revolve around two main issues: first, the violation of indigenous peoples’ rights; and second, direct harm to communities in general.”

In Bolivia, social impacts such as the violation of Indigenous rights have been identified in the Cuenca Madre de Dios, Nueva Esperanza Area Lot 1 project, which has faced numerous complaints regarding pressure on the Toromona, an uncontacted Indigenous group in northern La Paz. According to the Tacana Indigenous people, these activities have jeopardized the Toromona’s survival due to hydrocarbon exploration in the area. Requests have been submitted to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights for protective measures. Additionally, two road infrastructure projects—the San Borja–San Ignacio de Moxos Road and the Rurrenabaque–Riberalta Road—have been subject to claims for community and environmental damage. The former project destroyed potable water services, while the latter caused deforestation and pollution, affecting the Palmar Aguas Negras community of the Yuracaré Indigenous people. There have also been serious allegations of illegal trafficking of jaguar fangs.

The socio-environmental impacts in Colombia have been particularly noted in the extractive sectors, such as mining and hydrocarbon exploration. For example, the Buriticá Mine project was reported by the Collective on Chinese Financing and Investments, Human Rights, and the Environment (CICDHA) in February 2022 for structural damage to nearby homes caused by explosives, soil and water contamination from chemical use, adverse effects on community health, and harm to wildlife. Similarly, hydrocarbon projects like Bloque Llanos 69 and Sector OMBU were halted after conflicts with local communities due to socio-environmental damages. The former was denied an environmental license, while the latter was suspended by the company following intense clashes between the community and law enforcement over persistent environmental violations.

“The most recurrent environmental impacts were soil and water source contamination, deforestation and harm to protected areas, as well as the initiation of projects without the corresponding environmental permits.”

In Ecuador, socio-environmental impacts have also been associated with extractive sectors, particularly hydrocarbon exploration. The Tarapoa (Bloque 62) project faced allegations of harming Indigenous communities in the Waiya River basin and local farmers due to activities conducted without prior consultation and resulting pollution. Similarly, the Bloque 14 project was criticized by the Waorani Miwaguno community for gas flaring practices and their environmental consequences. The Bloques 79 and 83 project was suspended after Indigenous communities in voluntary isolation opposed its operations, citing significant socio-environmental impacts.

Extractive activities like hydrocarbon exploration have also raised socio-environmental concerns in Perú. Companies operating the Lote X and Lote 1AB/192 projects were sanctioned by the Environmental Oversight and Enforcement Tribunal of the Environmental Evaluation and Oversight Agency (OEFA) for failing to comply with mitigation commitments. The Lote 8 project faced community complaints for omitting the prior consultation mechanism.

In Venezuela, similar socio-environmental issues have arisen in hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation projects within the Orinoco Oil Belt. The Campo Carabobo project has been reported for restricting Indigenous Kari’ña and Warao access to their territories and causing environmental harm due to oil spills. The Bloque Junín 1 project has faced similar allegations, with frequent oil spills affecting nearby communities and ecosystems.

In Bolivia, socio-environmental impacts were primarily linked to the hydrocarbon extraction project Cuenca Madre de Dios, Área Nueva Esperanza Lote 1, and road infrastructure projects Carretera San Borja – San Ignacio de Moxos and Carretera Rurrenabaque – Riberalta.

In Colombia, impacts occurred mainly in extractive projects, including the gold mining project Buriticá Mine and hydrocarbon extraction projects Bloque Llanos 69 and Sector OMBU.

In Ecuador, socio-environmental issues were linked mainly to hydrocarbon extraction projects such as Tarapoa (Bloque 62), Bloque 14, and Bloques 79 and 83.

In Peru, socio-environmental concerns arose from hydrocarbon extraction projects such as Lote X, Lote 1AB/192, and Lote 8.

In Venezuela, socio-environmental impacts were reported specifically in hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation projects in the Orinoco Oil Belt, including Campo Carabobo and Bloque Junin 1.

Given the information outlined, it is crucial to address not only who bears the responsibility for protecting the rights of affected communities and ensuring environmental safeguards but also how and through what mechanisms such protection should be exercised.

Failures in both social and environmental management can primarily be attributed to the states of the Andean region. In many cases, the prior consultation mechanism established by ILO Convention No. 169, which guarantees Indigenous communities the right to be informed and to voice opinions on decisions affecting them, has been omitted. This omission, sometimes deliberate, has often been disguised as a mere socialization of projects.

“What level of responsibility do Chinese companies share in socio-environmental impacts resulting from their projects? While the responsibility to protect social and environmental rights rests with the states, companies are obligated to respect these rights.“

States are the principal guarantors of citizens’ rights and are obligated to provide prompt and effective mechanisms for complaints and redress in cases of violations. As evidenced in the projects discussed, successful cases exist where communities have been fully protected, while others have required international interventions for effective safeguarding. The degree of institutional strength and commitment varies across countries.

Regarding environmental impacts, states must protect the environment through international agreements and operational mechanisms for supervision, investigation, and sanctions for violations.

To what extent do Chinese companies share responsibility for socio-environmental impacts arising from their projects?

While protecting social and environmental rights is the sole prerogative of states, companies are responsible for respecting these rights. Significant efforts have been made to integrate companies into this framework through the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Various states, including Colombia and Peru, have adopted national action plans incorporating mechanisms to implement these principles. China has also included a chapter on businesses and human rights in its National Human Rights Action Plan.

In conclusion, the emphasis on shared responsibility between Chinese companies and Andean countries regarding socio-environmental impacts is essential. Only through synchronized efforts to protect and respect community rights can these investments foster mutually beneficial relationships.

“Synchronization between the protection and respect of community rights by both states and Chinese companies is key to fostering a mutually beneficial relationship through these investments.”

Related Publications: