China’s Communication with a Latin America Audience

China in Latin America and the Caribbean: Digital Diplomacy During COVID-19

The emergence of the global health crisis brought about by COVID-19 placed the People’s Republic of China clearly in the headlines of the world’s media. This was not simply due to the first registered cases of the virus occurring in the Chinese city of Wuhan. Once the first reports of a global spread of infection came out, it undertook a strategy of assistance and international cooperation mechanisms to face the crisis, now known as “mask diplomacy”.

Countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are among the worst affected by the pandemic, yet they are also among those to have benefited most from Chinese assistance and cooperation. It should be noted that this support is not only channeled at a bilateral level, but multilaterally through regional entities like the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC). Furthermore, it is not restricted to traditional channels between states, but involves a multiplicity of actors and elements—such as the use of digital technologies—that makes it necessary to clarify the diplomatic context in which this scenario is framed.

The purpose of this study is to examine how the COVID-19 crisis has impacted the development of China’s digital diplomacy in LAC, specifically the implementation of Twitter as a foreign policy tool, and to contrast it with the characteristics of its public diplomacy. To develop this view further, a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods was used. For the former, the “Twitter Advanced Search” and “Twitonomy” tools were used in the compilation of statistical data for each of the Twitter accounts studied. For the latter, a content analysis approach was implemented, identifying the most relevant topics and affording a more complete analysis of the information collected during the study period (January – June 2020).

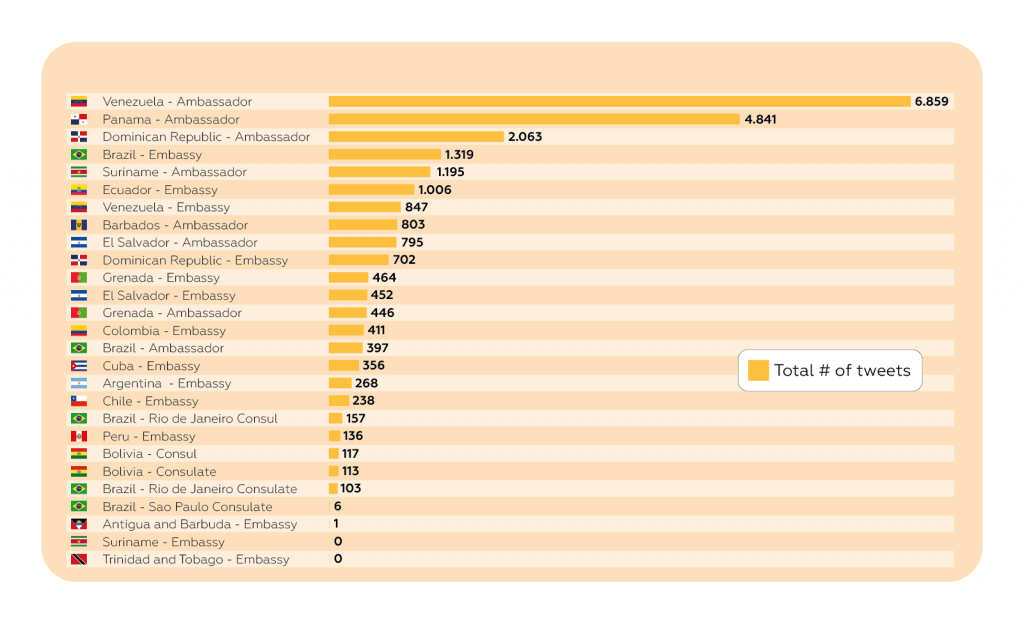

Of China’s 25 diplomatic missions based in LAC, only 17 have Twitter accounts. Combining both missions and representatives, the total increases to 27, 3 of which were inactive during the study period: Antigua and Barbuda (@ChinaEmbAntigua); Suriname (CHNEmbSuriname) and Trinidad and Tobago (@ChineseEmbinTT).

What do we mean by Public and Digital Diplomacy?

In contemporary international relations, public opinion plays a fundamental role, and communication is of the utmost importance. It is in this context that public diplomacy is developed differently to more traditional diplomacy. Communications are open and directed to foreign publics, as opposed to those of a secret nature held strictly between national governments. Although the development of both is distinct, their practice is by no means exclusive, as both have the same objective: the safeguarding of the national interest.

While academic literature offers no single definition of public diplomacy, it is widely defined as the process of communication between governments and a foreign public. Its aim—promoting an understanding about the country and its national ideals—is a means to gain international support to further the country’s national interests.[1]

To better understand this method of communicating with a foreign public, two types of public diplomacy have been identified. The first emphasizes one-way communication, which simply seeks to convey a message, whereas the second emphasizes a two-way approach in which a dialogue with the audience is established. This is characterized by the use of new digital technologies such as social networks.

In this digital environment, public diplomacy has found a valuable new tool to develop, and the virtual platforms offered by social networks have had the greatest impact. The adaptation of public diplomacy in the digital age has led to the emergence of new terms such as “digital diplomacy”, “public diplomacy 2.0”, “cyber diplomacy” and “Twitplomacy”, among others. This raises the question whether we are facing a new kind of diplomacy. Academic literature offers no answer in this regard yet, as what has happened thus far is simply the digitization of public diplomacy. To summarize, the most fitting term when attempting to understand the current state of the relationship between public diplomacy and digital technologies is therefore the “digitalization of diplomacy”.

China’s Approach to Public Diplomacy

From the second decade of the 21st Century, China began to take its first steps towards institutionalizing the practice of public diplomacy. Although the idea behind public diplomacy (公共外交) was already present through China’s soft power strategies, the use of this term in the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is given for the first time in a report presented by President Hu Jintao to the 18th CCP National Congress in November 2012. A year later, then newly appointed president Xi Jinping, embracing the term under the proposal of the “Chinese Dream” (中国梦) or what is known as the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (中华民族的伟大复兴), would institutionalize the concept in his speech at a high-level conference on propaganda and ideology. President Xi has highlighted China’s prerogative in the international projection of its image under the slogan “tell China’s story well” (讲好中国故事), which would go on to become one of the guiding principles of its public diplomacy. This concept would become intricately linked to the development of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) under which China seeks to significantly raise its international profile.

An analysis of how China develops its public diplomacy sheds light on the assumptions on which it bases its creation. In the words of German author and academic Falk Hartig: “How does China see itself in an international context? Mainly misunderstood. How does it perceive the international environment? Potentially hostile. And how does it want to be seen by the world? As a friendly, peaceful and reliable partner.” [2]

The objective of Chinese public diplomacy, like that of any country, is to safeguard its national interests, and for the CCP that safeguard depends on how it is perceived in the international system. Understandably, the Chinese government manages its public diplomacy carefully, providing clear guidelines and distinguishing two approaches that operate in complementary ways. A proactive approach, associated with the image it wants to project to the world, works alongside a reactive approach that tends to correct any negative external images, particularly when due to misunderstandings or misperceptions, as defined by the CCP.

Chinese public diplomacy represents a kind of hybridization when it comes to communications with a foreign public. Although its use of digital technologies has grown over the years, and in particular social networks, communication tends to be one-way, seeking only to convey a message.

The development of China’s digital diplomacy in LAC during COVID-19

- Dates of account creation and verification

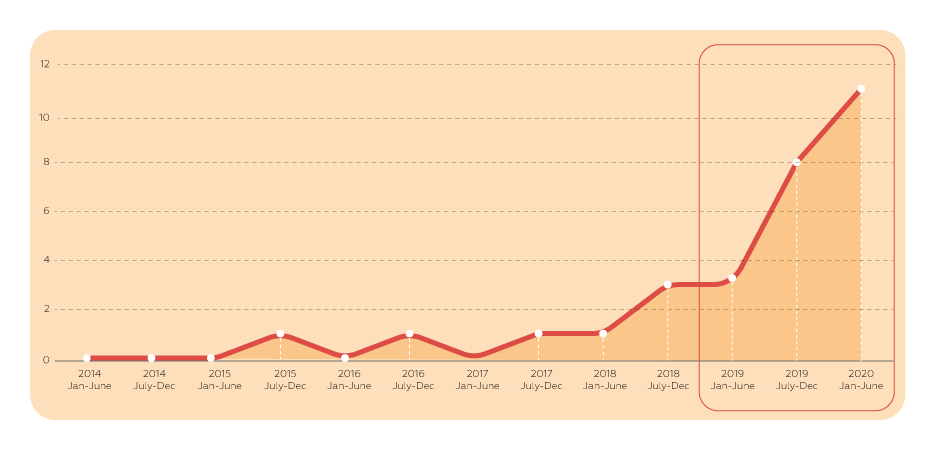

The first Twitter account created by a Chinese representative in LAC that has been active since its creation is that of the Chinese Ambassador to Brazil (@WanmingYang), on November 4, 2015. After this, the creation of Twitter accounts by China’s diplomatic missions in the region remains low until December 2017, at one per year. In 2018 there is a slight increase, with the creation of three accounts during the year. A significant increase then begins to occur from 2019, with an average of one to two accounts created every two months. The situation then changes dramatically between January and June 2020 with the creation of one to three new accounts per month, which could be explained by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on China’s image.

Click here to see accounts creation date chart

Only 33% (9) of the 27 accounts analyzed hold Twitter’s “blue verified badge” for authenticity, a status that generates confidence among the public. It denotes a legitimate source, and the verification process is carried out at the request of the account holder. It is striking therefore that despite the high activity of other accounts held by China’s diplomatic missions in the region, the process has not been adopted universally.

- Account activity and number of followers

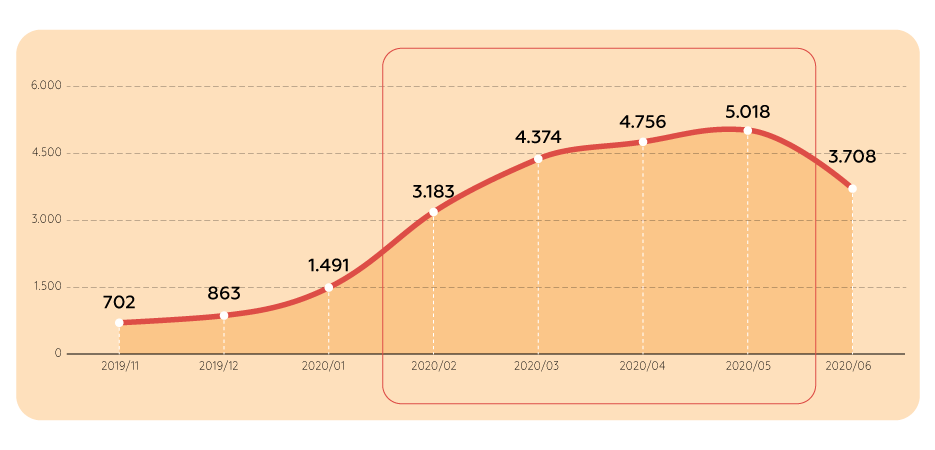

An analysis of account activity by volume of monthly tweets shows evidence of an increase in activity in line with the evolution of the COVID-19 crisis. [3] After the detection of the first cases of a “viral pneumonia” towards the end of 2019 in Wuhan, monthly account activity begins to double from January 2020. Between February and March, a significant increase in Twitter activity coincides with the confirmation of the first cases of infection in LAC —Brazil being the first in february 26th— and the spread of the virus at a global level, which leads to the declaration of a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11. This trend continues to rise in March and April as cases continue to rise both in LAC and globally, and criticism towards the Chinese government and the WHO intensifies from several countries —particularly the United States— for the handling of the Pandemic.

The upward trend in Twitter activity of China’s diplomatic mission accounts in LAC reaches its peak in May, corresponding not only to an increase in infections, but to the escalation of political and trade tensions between the US and China. In June, there is a decrease in Twitter activity as COVID-19 contagion levels decelerate globally.

In each of the accounts analyzed, the same general behavior was identified, including a rise in activity during the period studied. A significant disparity was observed however in the overall number of tweets for each of the accounts. The most active accounts (over 1,000 tweets in total) belonged to China’s ambassadors to Venezuela, @Li_Baorong (6,859 tweets); Panama, @weiasecas (4,841 tweets); Dominican Republic, @EmbZhangRun (2,060 tweets), its embassy in Brazil, @EmbaixadaChina (1,292 tweets); and the ambassador in Suriname, @AmbLiuQuan (1,195 tweets). The remainder produced less than 1,000 tweets each, although their activity increased throughout the period of observation.

- Number of tweets per account

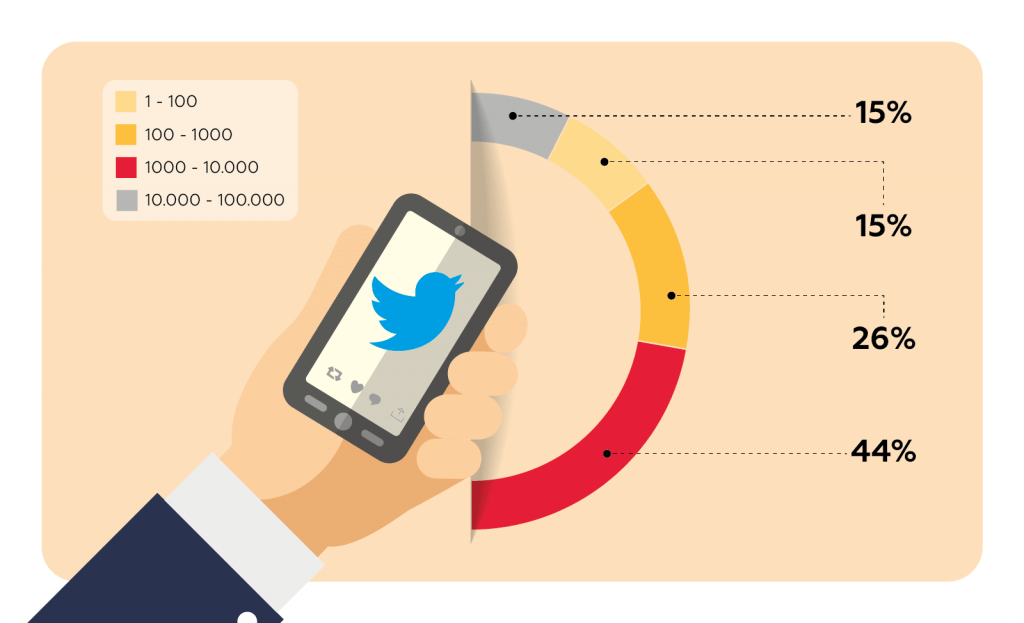

While the overall number of followers is important due to the reach of these messages, the engagement they prompt is even more so, thanks to the creation of a communications network. More than half of the 27 accounts studied had between 1,000 and 100,000 followers, although this range is not especially significant considering Twitter’s 326 million users worldwide, according to the 2020 Global Digital Overview. One notorious absence is an account for China’s diplomatic mission to Mexico, given its status as the second most active country on Twitter in LAC after Brazil.

- Overall number of followers

How China’s diplomatic missions in LAC engage on Twitter

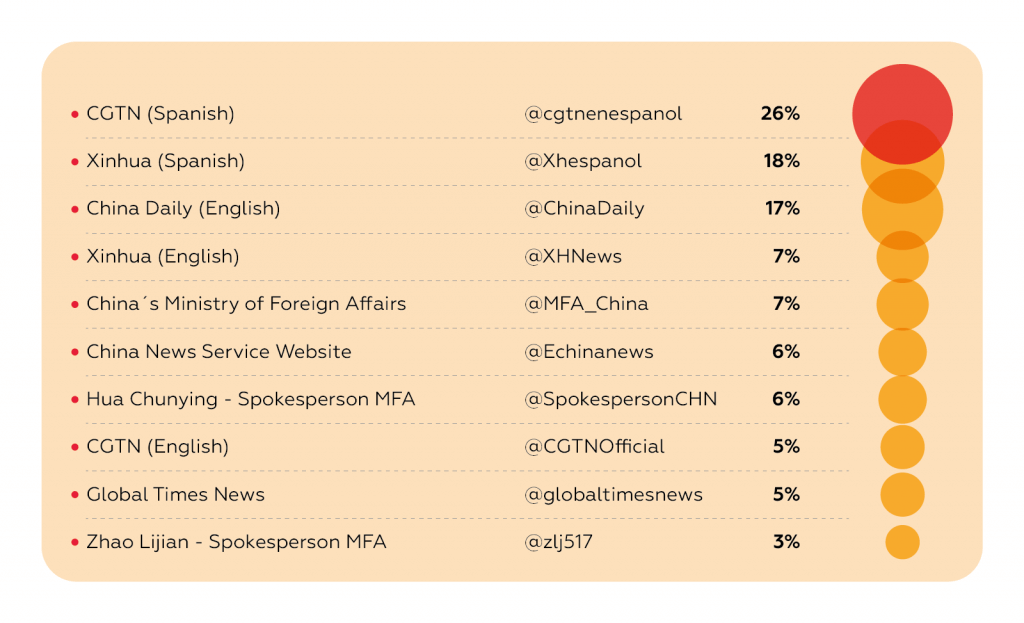

Chinese government entities, in particular the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, its spokespersons, and state-owned media are the most retweeted users. This is hardly surprising considering the purpose of retweets, as the Chinese government’s priority is to be the guiding hand and voice in the management of its international image.

- Most retweeted users

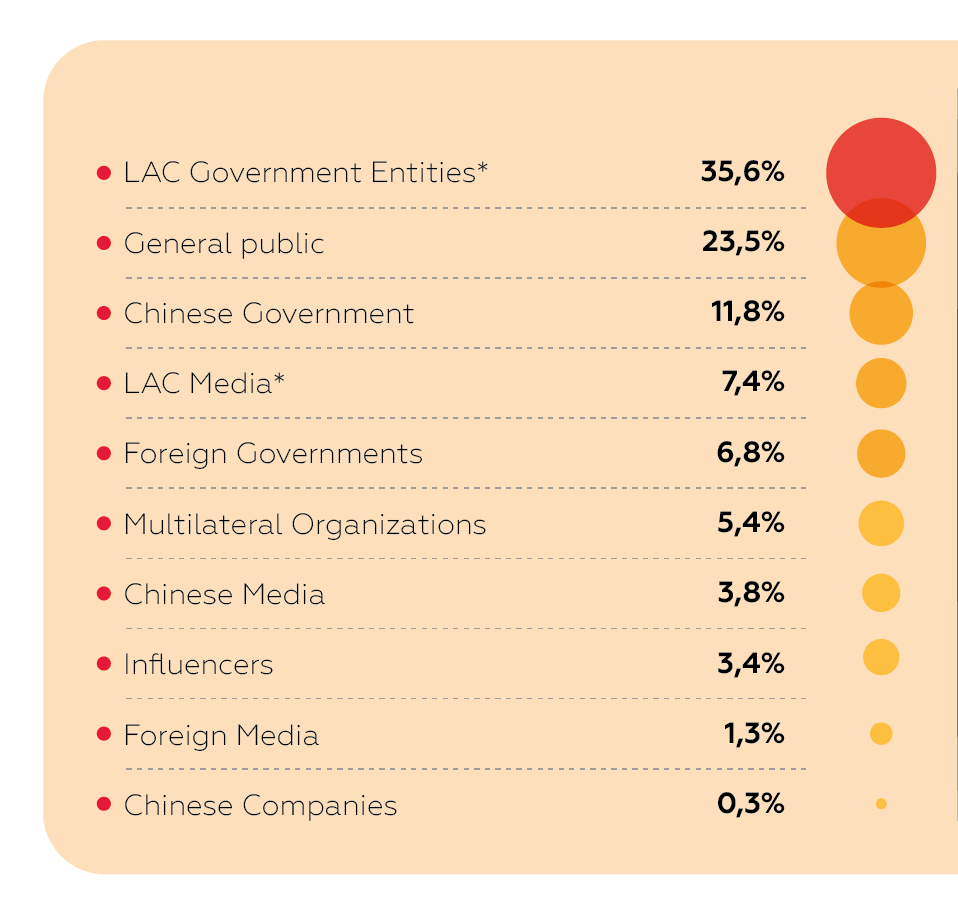

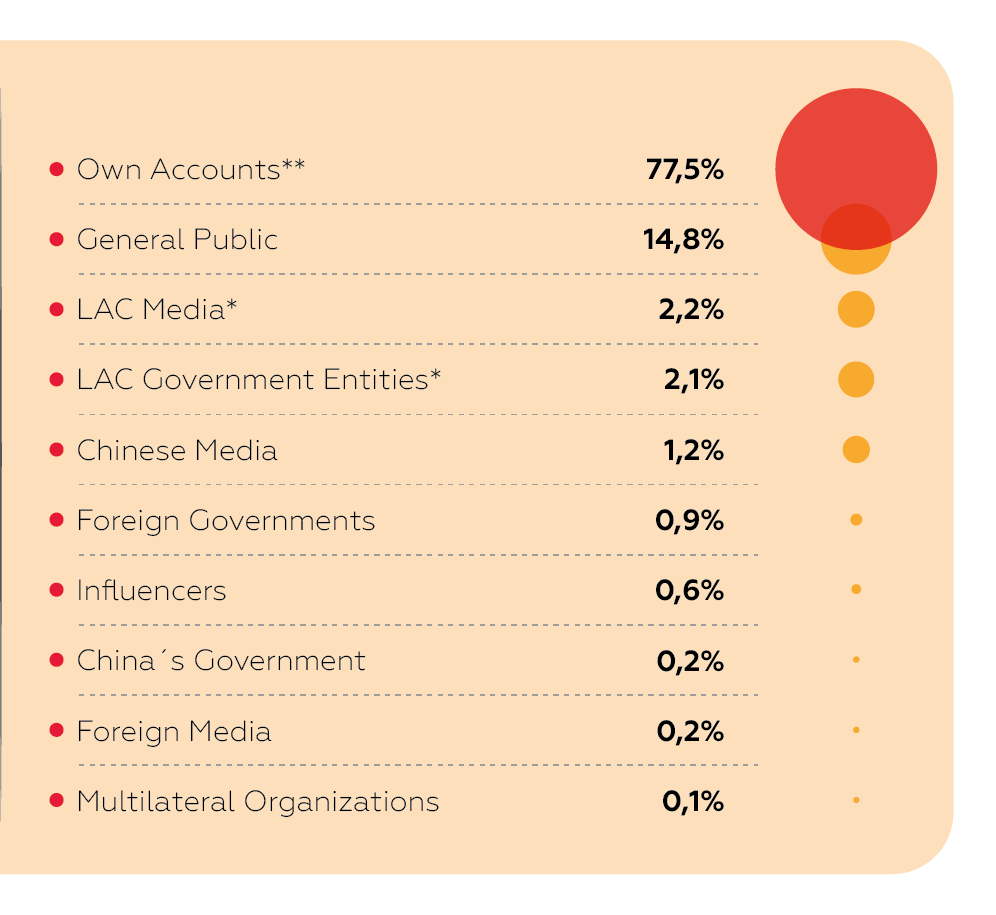

- Users: most mentioned and with highest number of responses

Both of the following graphs show that the foreign public (referring to the general populace as the main focus of public diplomacy) prompts the second-highest levels of engagement within China’s creation of a communication network as it develops its digital diplomacy in the region. In first place are mentions of government entities (as indicated in the first graph) and from their official accounts (second graph). In third place, the media of the country where the mission is located (both graphs). The content of the tweets refers to both tangible[4] and intangible [5] methods of support and cooperation by the Chinese government to each of the countries in question. By considering these three pieces of evidence together, we can see that in addition to simply communicating a message, a dialogue is created with the foreign audience, fulfilling the primary objective of public diplomacy.

Click here to see details about the categories.

- Highest number of responses (Jan – Jun 2020)

Of the 27 Twitter accounts analyzed, it should be noted that only 16 adopted this type of dialogue with the foreign public. On a scale of low, medium and high, the most active accounts in this dialogue were that of the Consulate General in Santa Cruz, Bolivia (@ConsuladoCHNSC), and the ambassadors to El Salvador (@oujianhong), Panama (@weiasecas) and the Dominican Republic (@EmbZhangRun).

*Referring to the host country.

**Referring to Chinas Diplomatic representatives accounts

Click here to see details about the categories.

- Most used hashtags [6]

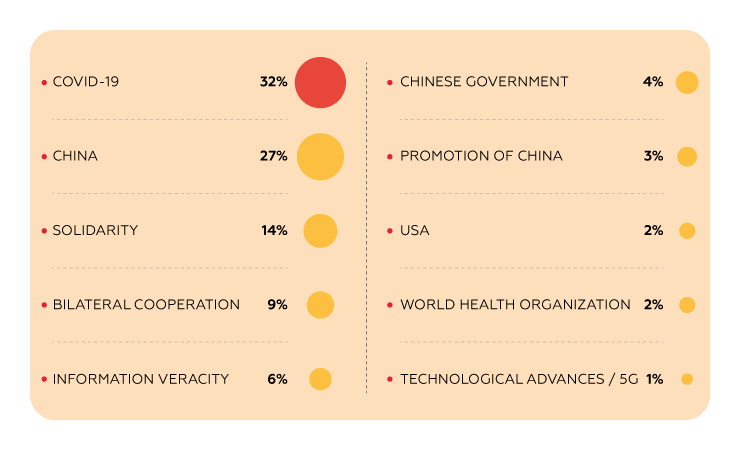

As the most used hashtag in the period of analysis, #COVID19 reflects the importance of the crisis to China’s digital diplomacy in LAC, reflecting its cross-cutting priority above other categories.

Click here to see details about the categories.

An analysis of hashtags relating to “China”, “solidarity” and “country cooperation”, together with the content of tweets highlighting how the pandemic was contained in China, and the country’s assistance and cooperation in LAC, shows a proactive approach to one of its main public diplomacy objectives: to improve and strengthen its image at an international level.

Similarly, hashtags referring to the “promotion of China”, “Chinese government” and “technological advances / 5G” all seek to generate interest in China in order to both deepen and strengthen economic ties and cooperation within LAC.

Together with the content of tweets, reactive hashtags linked to “accuracy of information”, “multilateral organizations” and “USA” seek not only to correct China’s image, but to present itself to the world—in contrast to the US—as a peaceful and reliable partner that wants harmony within the international system by highlighting the importance and defending the stability of multilateral organizations.

Although the content of all of China’s diplomatic mission accounts in LAC was generally aimed at protecting the country’s image, particularly in relation to tensions with the US government, it should be noted that there was a substantial difference in tone between the diplomatic missions (embassies and consulates) and diplomatic representatives (ambassadors and consuls), the latter adopting a more aggressive, defensive tone. The most antagonistic examples of US-related content came from China’s ambassadors to Grenada (@DrZhaoyongChen); Suriname (@AmbLiuQuan); Venezuela (@Li_Baorong) and the Consul General in Santa Cruz, Bolivia (@ WangJialei4).

It is important to highlight information not included in the analyzed content such as the BRI. As one of the defining policies of the Xi Jinping presidency, it is notable by its absence in the implementation of Chinese digital diplomacy in the region, especially given that 19 countries have signed cooperation agreements under the initiative.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis certainly advanced the development of China’s digital diplomacy in LAC. This is reflected in the increase of new Twitter accounts and an upsurge in content development by diplomatic missions in the region during the first half of the year. It is worth considering however the inactivity of many of them, and the non-existence of others such as Mexico, whose relations with China are important and long-standing.

There is no doubt that the development of China’s digital diplomacy in LAC reflects its approach to public diplomacy: the defense of its image in order to safeguard its national interests. However, the rivalry between the US and China is clearly reflected here, too.

Although the study was able to show the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the development of China’s digital diplomacy in LAC, new questions arise over certain behavioral particularities of the different Twitter accounts of China’s diplomatic missions in the region. Why is there a difference in rhetoric between its diplomatic missions and diplomatic representatives? Is this difference due to the diplomat’s personality and career trajectory? Is there a relationship between the development of China’s digital diplomacy and the bilateral linkages with the host country in question? Is there a correlation between the development of China’s digital diplomacy and a subregional strategy within LAC? It would certainly be interesting to address these issues in the future.

Click here to read about the methodology used for this analysis

Translated by Edward Longhurst-Pierce

Notes

[1] For definitions of public diplomacy, see Jan Melissen (Ed.), The New Public Diplomacy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)

[2] Hartig, F. (2016). How China Understand Public Diplomacy: The Importance of National Image for National Interests. International Studies Review, 18(4), 655-680. Doi: 10.1093/isr/viw007

[3] To analyze the trend of this item, the search range was extended from November 2019 to observe the incidence of the health emergency caused by Covid-19 in China’s public diplomacy.

[4] Humanitarian aid to populations at risk, donations of medical equipment, biosafety supplies, and virus tests.

[5] Training on prevention and health protection strategies against Covid-19, meetings, and conferences on advances in the management of infected persons, technical collaboration for advances in a possible vaccine.

[6] For the analysis of this information, a classification of the most relevant topics was made according to the use of labels and the content of the tweets, however, it should be noted that these are not exclusive categories but complementary.

References

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republico f China. Speech by State Councilor Wang Yi at the Special Videoconference between the Chancellors of China and Countries of Latin America and the Caribbean against COVID-19. Available here.

Melissen, J. (Ed.). The New Public Diplomacy. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)

Manor, I (2016) What is Digital Diplomacy, and how is it Practiced around the world. A brief introduction. Available here.

Manor, Ilan, “The Digitalization of Diplomacy: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Terminology,” Working Paper No 2. Oxford Digital Diplomacy Research Group (Jan 2018), Available here.

Nye, J. (1990). Soft Power. Foreign Policy (No. 80). doi:10.2307/1148580.

The 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Available here.

“Xi Jinping: Ideological work is an extremely important task for the Party.” Xinhua. Available here.

Belt and Road Initiative. Available here.

Hartig, F. (2016). How China Understand Public Diplomacy: The Importance of National Image for National Interests. International Studies Review, 18(4), 655-680. Doi: 10.1093/isr/viw007

Americas Society Council of the Americas. Report on Coronavirus in Latin America. Available here.

We are Social & Hootsuite (2020). 2020 Global Digital Overview. Available here.